Computational Complexity¶

All semester, we've been interested in algorithms for computational problems that:

Did polynomial work in the input size

Leveraged concurrency to achieve span (i.e., parallel speedup)

We've studied different algorithmic paradigms to try and achieve these two goals.

But, when is this actually possible?

What problems are solvable with polynomial work? Of those, which allow us to achieve a good parallel speedup?

Conversely, which problems aren't solvable with polynomial work?

Perhaps we could just avoid or approximate these, instead of trying to find efficient algorithms.

Why study Computational Complexity?¶

Why would we care about characterizing the difficulty of problems? Why not just do the best we can?

Given a problem $\mathcal{X}$ that we want to solve efficiently, we might not be able come up with a polynomial-work algorithm.

It would be better to say...

Computational Complexity¶

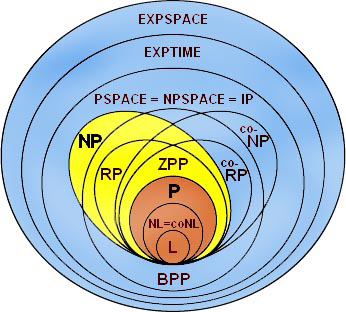

The field of computational complexity tries to characterize problems by resource complexity (e.g., work, span, space).

For example, we can say that the sorting problem is in the class of problems that can be solved in polynomial work. This class is refered to as class $\mathcal{P}$.

We'll define some basic complexity classes and look at how much progress has been made in the last 50 years or so.

Decision Problems¶

In our discussion, we will look at decision problems, i.e., computational problems with YES/NO answers.

This is not a big restriction, because if we can solve a decision problem we can solve the optimization version using binary search.

Example: Suppose we only have a decision version of MST: DECISION-MST

DECISION-MST outputs only True or False, True if the cost of the MST is $<= k$ and False otherwise.

Then we can find the $k$ that is the cost of the MST by performing a binary search on $k$. How do we choose a starting value for $k$?

This requires time polynomial in the input. Why?

For MST, we gave several very efficient algorithms (with work nearly linear in the input size).

We've seen many problems for which we've been able to develop efficient solutions.

Loosely, an efficient solution is one whose work is polynomial or better.

Inefficient Algorithms¶

Are there any problems for which we haven't seen efficient algorithms?

Yes - TSP and Knapsack.

Are there more efficient algorithms possible than what we've seen? Slightly, but the best we can do is essentially some kind of inefficient/exhaustive search over the solution space.

To justify such inefficient approaches, we'd like to give a superpolynomial lower bounds for TSP or Knapsack (or any problem for which we can't find an efficient algorithm).

Given our lack of ability to find efficient algorithms for these problems, it would be nice to be able to say that a polynomial solution is impossible.

Although, setting our egos aside, it would be even better to produce an efficient algorithm!

Complexity Classes¶

There are a number of very common/useful problems for which we can't seem to

A) come up with good algorithms, or

B) prove that no good algorithms exist.

Two more examples:¶

Satisfiability ($\mathcal{3SAT}$):

Given a logical formula $F(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$ that is written as a 3CNF ("CNF" stands for conjunctive normal form), is there an assignment of $x_1, \ldots, x_n$ such that $F$ yields evaluates to True?

$$(x_1 \vee x_2 \vee \neg{x_3}) \wedge (x_2 \vee x_3 \vee \neg{x_4})\wedge (x_1 \vee \neg{x_2} \vee x_4)$$Independent Set ($\mathcal{IS}$):

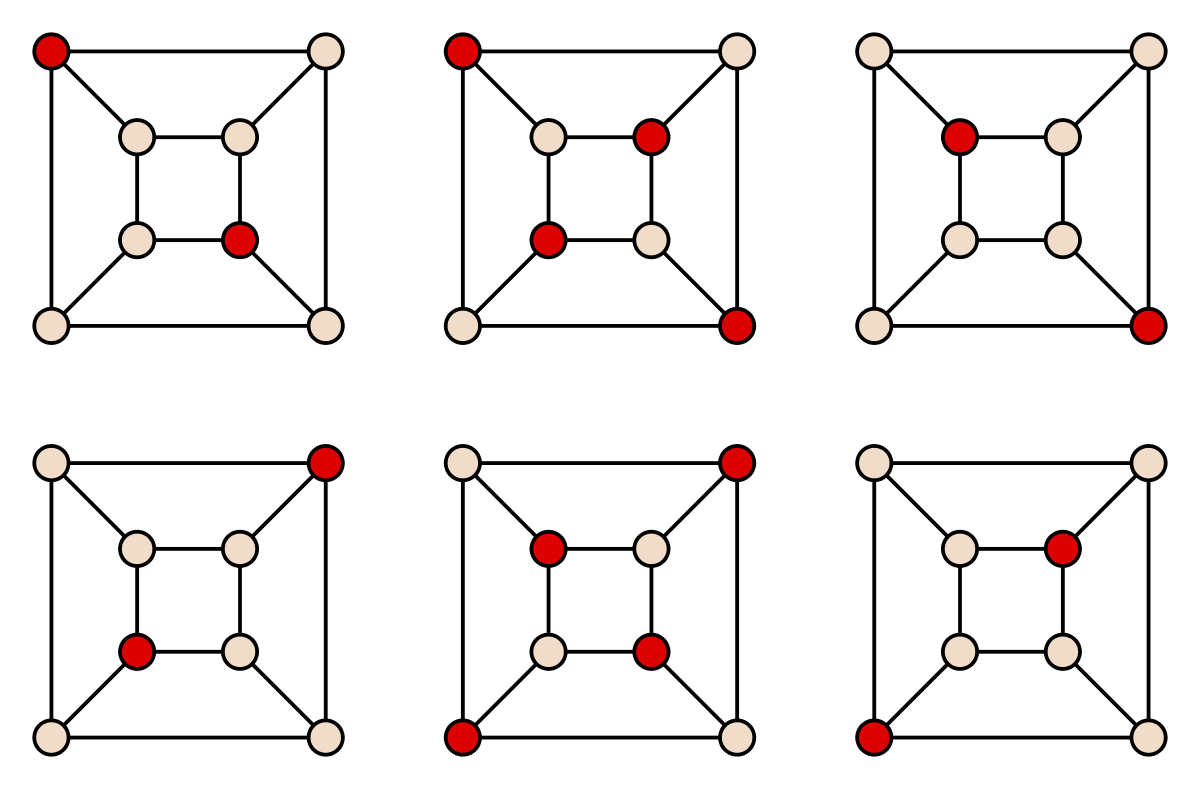

Given a graph $G=(V, E)$, is there a set $X\subseteq V$ of size at least $k$ such that no vertices $x, y\in X$ share an edge?

Checking versus Solving¶

There is an interesting fact about many of these problems that we can't seem to efficiently solve.

Given a solution, we can actually check whether or not the solution is correct very quickly. We just don't know how to produce a "YES" instance efficiently.

Examples¶

- $\mathcal{3SAT}$: Is there a truth assignment for which this boolean expression evaluates to

True?- Given a truth assignment for a formula $F$, we can easily plug it in and check it.

- $\mathcal{TSP}$: Is there a cycle that covers the graph with cost less than $k$?

- Given a proposed cycle, verify that is cycle, check if sum of weights is less than k.

- $\mathcal{Knapsack}$: Can a value of atleast $V$ be achieved without exceeeding the weight $W$?

- Given a set of items, sum up weight and value of all items.

- $\mathcal{Independent Set}$: Does the graph contain an independent set of size $k$?

- Given a proposed independent set $IS$, verify none of the vertices are neighbors. Return

Trueif $|IS| >= k$

- Given a proposed independent set $IS$, verify none of the vertices are neighbors. Return

Class $\mathcal{NP}$¶

Class $\mathcal{NP}$ is the class of problems for which we can efficiently check, given a candidate solution, whether that solution produces a YES answer.

By efficiently, we mean in polynomial time.

What does $\mathcal{NP}$ stand for?

$\mathcal{NP}$ stands for Nondeterministic Polynomial Time.

It means that if we are given a nondeterministic computer, we could solve the problem in polynomial time.

Nondeterminism¶

Nondeterminism is a wonky idea from computer theory.

Deterministic Computers

Classical computers are deterministic. Every step is determined exactly by all preceding steps.

Nondeterministic Computers

In a nondeterministic computer, the next step can be determined by information outside of the computer.

When a nondeterministic algorithm is presented with a choice, it can automatically choose the optimal choice, whether or not it has enough information to actually know that choice is optimal.

This is somewhat akin to if god played chess. God would know automatically the optimal move for every move of the game.

How does this all relate back to the class NP?

Since all problems in NP are verifiable in polynomial time, one potential algorithm for solving any of these problems is to attempt to verify all possible solutions – a brute force approach.

A nondeterministic algorithm granted the magical power of optimal choice can simply choose the correct answer to verify rather than searching for it, and following the polynomial verification, will be done.

Class $\mathcal{NP}$¶

$\mathcal{P}$ is the class of problems for which we can compute solutions directly with polynomial work.

Now we know that $\mathcal{P}\subseteq\mathcal{NP}$, since, for any problem in class $\mathcal{P}$, we can efficiently verify a solution by constructing it in polynomial time.

But does $\mathcal{P} = \mathcal{NP}$?

Or more informally, is it substantially harder to solve a problem than to check a solution to it?

Reductions¶

Interestingly, many of these problems reduce to one another.

Recall that a problem $\mathcal{X}$ is polynomial-time reducible to a problem $\mathcal{Y}$ if we can perform

1) an input transformation from $\mathcal{X}$ to $\mathcal{Y}$ and

2) an output transformation from $\mathcal{Y}$ to $\mathcal{X}$ with polynomial work.

We can then solve $\mathcal{X}$ by reducing it to $\mathcal{Y}$, solving $\mathcal{Y}$, then transforming the output back to a solution for $\mathcal{X}$.

This shows that $\mathcal{X}$ "no harder than" $\mathcal{Y}$, because we wouldn't be able to solve $\mathcal{X}$ using $\mathcal{Y}$ if $\mathcal{X}$ were a harder problem than $\mathcal{Y}$.

Example, we can reduce MIN to SORTING.

Thus MIN is no harder than sorting.

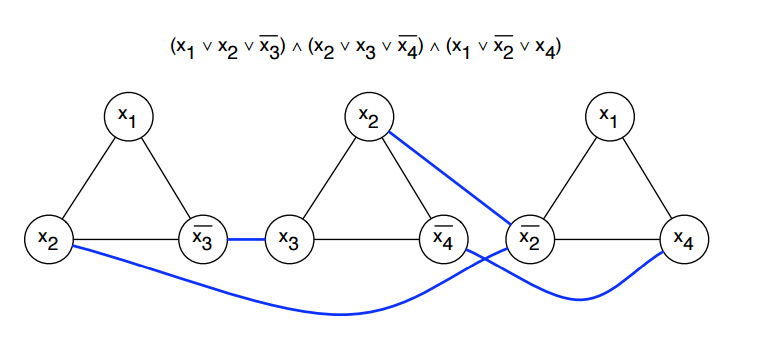

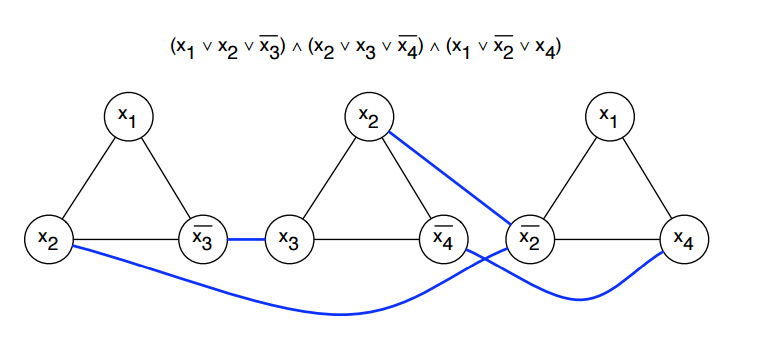

Example: $\mathit{3SAT} \leq \mathit{IS}$¶

Any logical formula can be written in 3CNF, which has clauses AND'ed together with each clause OR'ing 3 literals.

For example:

$$ F(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4) = (x_1 \vee x_2 \vee \neg{x_3}) \wedge (x_2 \vee x_3 \vee \neg{x_4})\wedge (x_1 \vee \neg{x_2} \vee x_4).$$If $F$ is an input instance to $\mathit{3SAT}$, then we want to know if there is any assignment of $x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4$ that evaluates to TRUE.

To show that $\mathit{3SAT} \leq \mathit{IS}$, we need to show that we can reduce from 3SAT to Independent Set and solve Independent Set to get a solution for 3SAT.

Reduce $\mathit{3SAT}$ to $\mathit{IS}$¶

Given a logical formula $F$, how do we create a graph in which an independent set tells us about the satisfiability of clauses in $F$?

For a formula $F$ with $n$ variables and $k$ clauses, we construct a graph representing $F$ as follows:

- Create a Graph $G_F$ containing a vertex for every literal.

- Connect all 3 literals in each clause by edges between them

- This ensures that only one literal per clause will chosen, corresponding to the literal to be set to

True. (we only need one literal per clause to beTruefor the clause to beTrue.)

- This ensures that only one literal per clause will chosen, corresponding to the literal to be set to

- Add an edge between every literal and its negation.

- This ensures that conflicting literals can not be chosen. If $x$ chosen, then we can not also choose $\bar{x}$.

- Set $k$ to be the number of clauses.

- This forces us to choose one literal per clause.

An independent set $X$ in $G_F$ corresponds to a set of literals in $F$.

We've set the size of the satisfying independent set in $G_F$ is $k$, corresponding to at most one literal per clause.

We can never choose a pair of vertices in the independent set with opposite literals since they are connected by an edge.

Thus if we set all literals corresponding to the vertices in $X$ to

TRUE, we will satisfy $|X|$ clauses.

So, $F$ is satisfiable if and only if there is an independent set of size $k$ in $G_F$.

So what's the big deal if one problem in $\mathcal{NP}$ reduces to another?

$\mathcal{P} = \mathcal{NP}$ and NP-Completeness¶

Leonid Levin and Steve Cook showed in the early 1970s that for any problem $\mathcal{X} \in \mathcal{NP}$, $\mathcal{X} \leq \mathit{SAT}$.

So, $\mathit{3SAT}$ is $\mathcal{NP}$-complete.

In other words, for any problem $\mathcal{X} \in \mathcal{NP}$, $\mathcal{X}$ can be reduced to $\mathit{3SAT}$.

Since $\mathcal{X}$ is no harder than $\mathcal{3SAT}$, if an efficient solution were found for $\mathcal{3SAT}$, then we could efficiently solve $\mathcal{X}$.

Consequences

If we could demonstrate a lower bound that $\mathit{3SAT}$ requires super-polynomial work, then we would prove that $\mathcal{P} \neq \mathcal{NP}$.

If we came up with a polynomial work algorithm for $\mathit{3SAT}$, then we would prove that $\mathcal{P} = \mathcal{NP}$.

But we haven't been able to do either of these things, so far.

Implications of reduction¶

Does our reduction from $\mathit{3SAT}$ to $\mathit{IS}$ tell us anything interesting?

That Independent Set is $\mathcal{NP}$-complete!

Since we can reduce from $\mathit{3SAT}$ to $\mathit{IS}$, if an efficient solution were found for $\mathit{IS}$, we would have an efficient solution for $\mathit{3SAT}$, and for all problems in $\mathcal{NP}$ by extension!

The $\mathcal{NP}\texttt{-complete}$ family¶

What does this have to do with TSP or Knapsack?

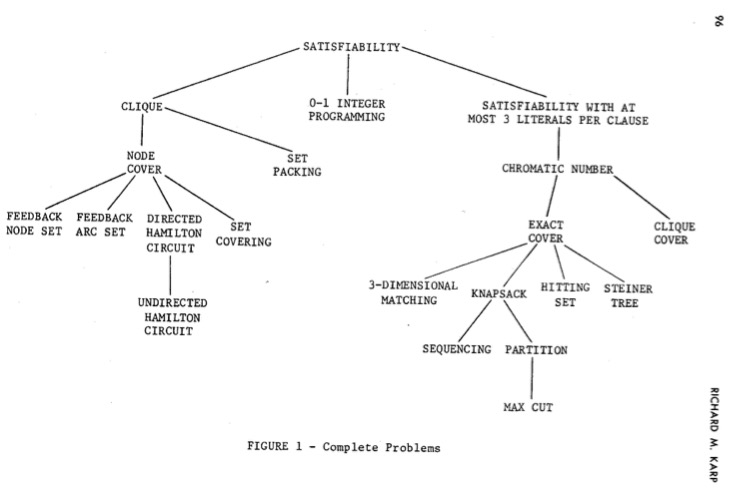

After Levin and Cook showed the satisfiability problem was $\mathcal{NP}\texttt{-complete}$, Richard Karp used reductions to show 21 different problems were all $\mathcal{NP}\texttt{-complete}$.

Implications¶

There is some inherent similarity between all problems in the set $\mathcal{NP}$-complete since an efficient solution to any leads to an efficient solution to all.

This means there is something fundamental here about the complexity of these problems and the nature of problem solving in general.

Is it substantially more difficult to solve a problem than to verify a solution?

Or, if it is easy to verify a solution, does that imply that there is some efficient way of generating that solution in the first place?

For example, it (... a practical algorithm for solving an NP-complete problem (showing P=NP)) would transform mathematics by allowing a computer to find a formal proof of any theorem which has a proof of a reasonable length, since formal proofs can easily be recognized in polynomial time. Example problems may well include all of the CMI prize problems.

-- Stephen Cook Official P vs NP problem statement

$\mathcal{NP}$-completeness doesn't provide us with concrete answers but it does help us understand the relative difficulty of problems. We currently have many thousands of such problems!

Parallelism?¶

Can we parallelize and solve $\mathcal{NP}$-complete problems?

Since the definition of span doesn't really care about the number of processors, we can solve problems in $\mathcal{NP}$ using brute force with polynomial span. This is because the definition of $\mathcal{NP}$ ensures that we can efficiently check candidate solutions.

A more interesting question is whether we can effectively parallelize problems in $\mathcal{P}$. That is, for any problem $\mathcal{X}$ that is solvable in polynomial work, does it also have low span?

Class $\mathcal{NC}$¶

Let $\mathcal{NC}$ denote the set of all problems with span $O(\log^c n)$ for some constant $c$ using a polynomial number of processors.

We know that $\mathcal{NC}\subseteq \mathcal{P}$, but is $\mathcal{P}\subseteq\mathcal{NC}$?

What does this statement imply?

If $\mathcal{P}\subseteq\mathcal{NC}$, then every problem in $\mathcal{P}$ is parallelizable.

$\mathcal{P}$-complete¶

As with $\mathcal{NP}$, it's possible to define $\mathcal{P}$-complete problems.

The Circuit Value Problem ($\mathit{CVP}$) asks, for a given circuit on AND, OR, and NOT gates along with inputs, does the circuit produce an output of 1?

$\mathit{CVP}$ is $\mathcal{P}$-complete.

As with $\mathcal{NP}$, we have a long list of $\mathcal{P}$-complete problems. We cannot find polylogarithmic span algorithms for any of them, nor can we prove that it is not possible to come up with such algorithms.

We have just looked at two complexity classes, but this area is quite deep.

P vs. NP as explained by AI¶

ChatGPT Prompt: Explain the P vs NP problem as a poem.

P and NP, oh what a mystery,

Two classes of problems, oh so perplexing to see,

P is the class where solutions are easy to find,

But checking them takes some time.

NP is the opposite, solutions are hard to come by,

But once found, they can be verified with a single try,

Together, they form a dichotomy,

That has puzzled the brightest minds in computer science history.

P vs NP, a question that's been asked for many years,

Is every NP problem also in P? Or are there some that never appear?

No one knows the answer, but we can still try,

To solve this conundrum, and to unravel this knot of a problem that's so sly.

So let us all ponder, and let our minds roam,

To find the solution, to this question that's still unknown.