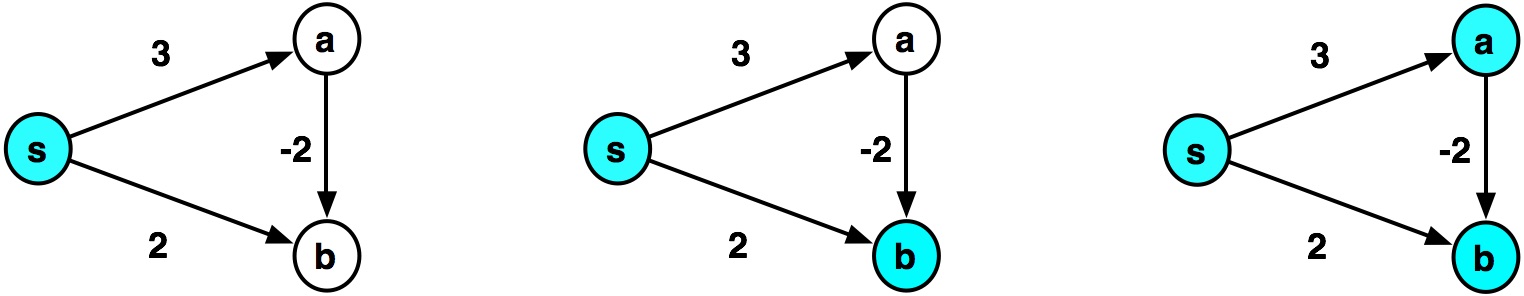

Recall that Dijkstra's algorithm assumed positive edge weights. Why?

Dijkstra's property¶

For any partitioning of vertices $V$ into $X$ and $Y = V \setminus X$ with $s \in X$:

If $p(v,x) = \min_{x \in X} (\delta_G(s,x) + w(x,v))$, then

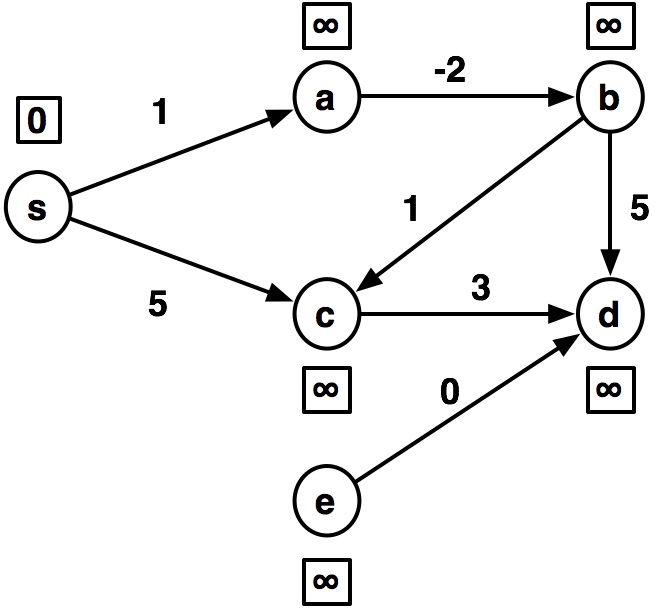

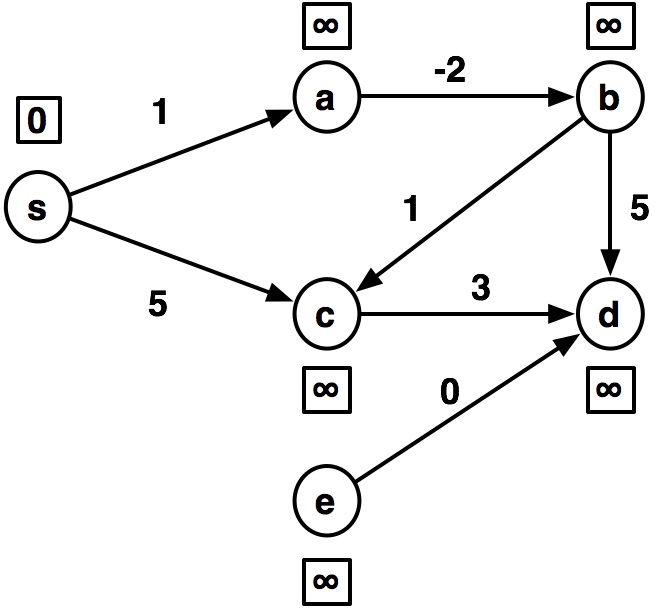

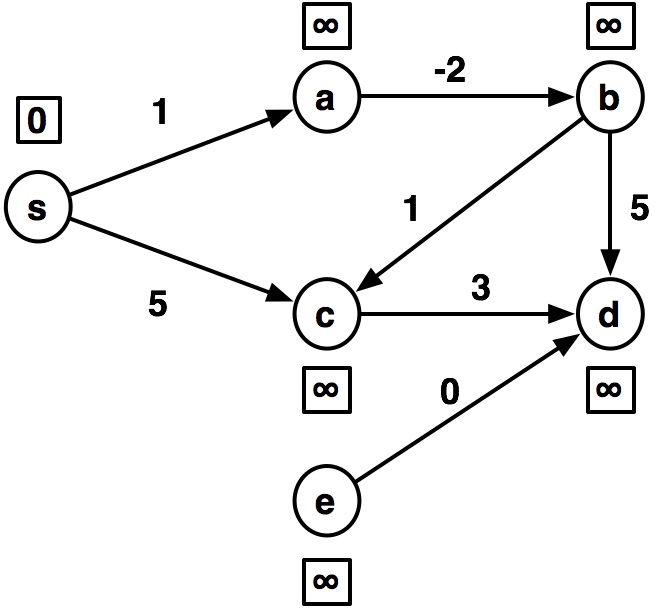

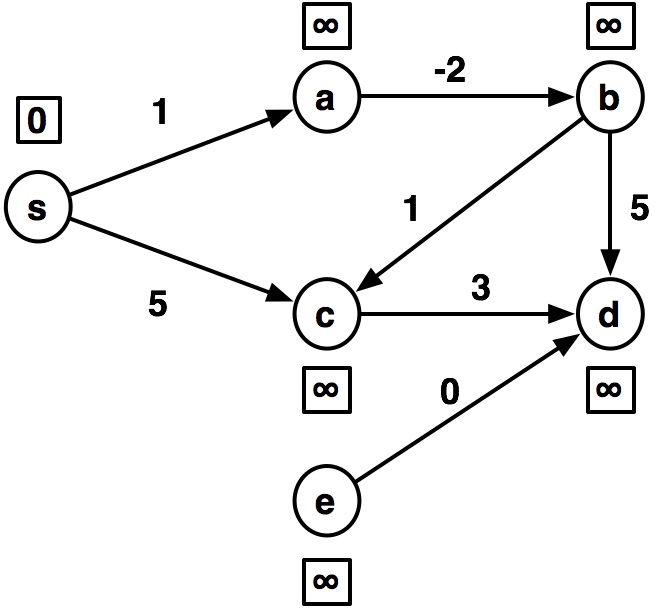

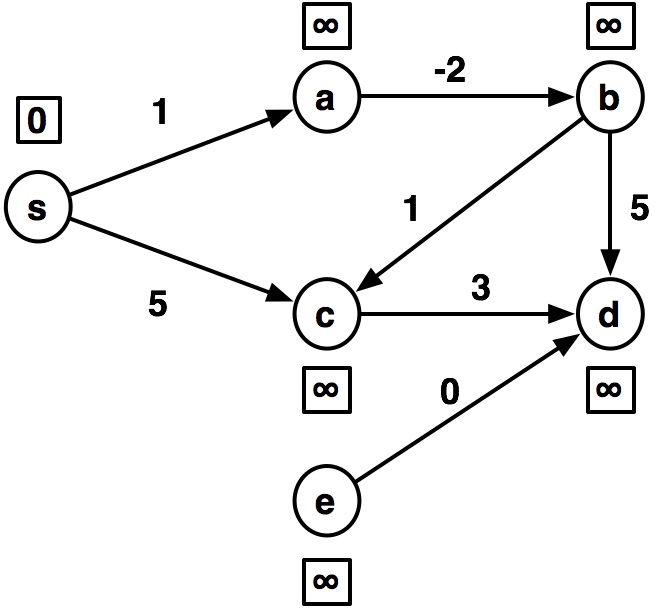

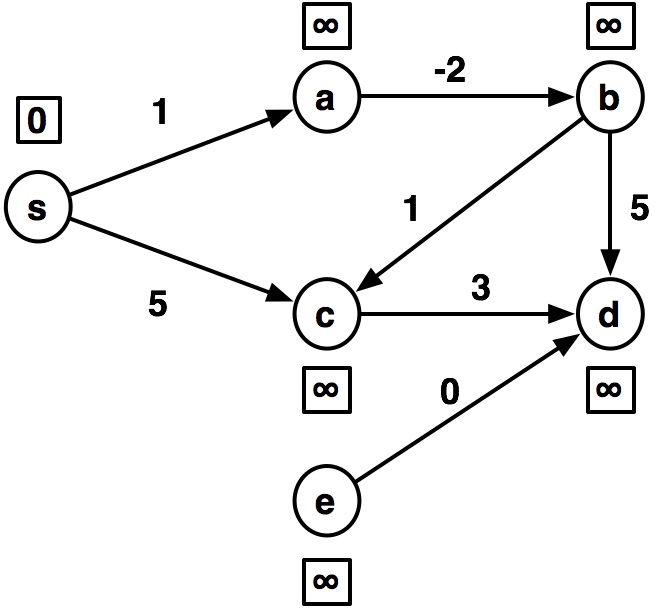

$$\min_{y \in Y} p(y) = \min_{y \in Y} \delta_G(s, y)$$What goes wrong in this example?

- At the second step, Dijkstra assigns $\delta(s,b)\leftarrow 2$

- When $a$ is visited in the third step, $b$ would be added to the heap with distance $1$.

- But, when $b$ is popped off the heap the second time, it is ignored, because of:

if node in visited: # Already visited, so ignore this longer path return dijkstra_helper(visited, frontier)

With negative edge weights, paths can get shorter as we add edges!¶

Why would we ever have a graph with negative edge weights?

- finance: cost versus profit

- chemistry: attractive vs repulsion

Dealing with negative edge weights¶

Since paths can get shorter as we add edges, we'll modify Dijkstra to instead keep track of both the weight and the number of edges in a path.

$\delta^k(u,v)$: weight of shortest path from $u$ to $v$ considering paths with at most $k$ edges.

- If no such path exists, $\delta^k(u,v)=\infty$

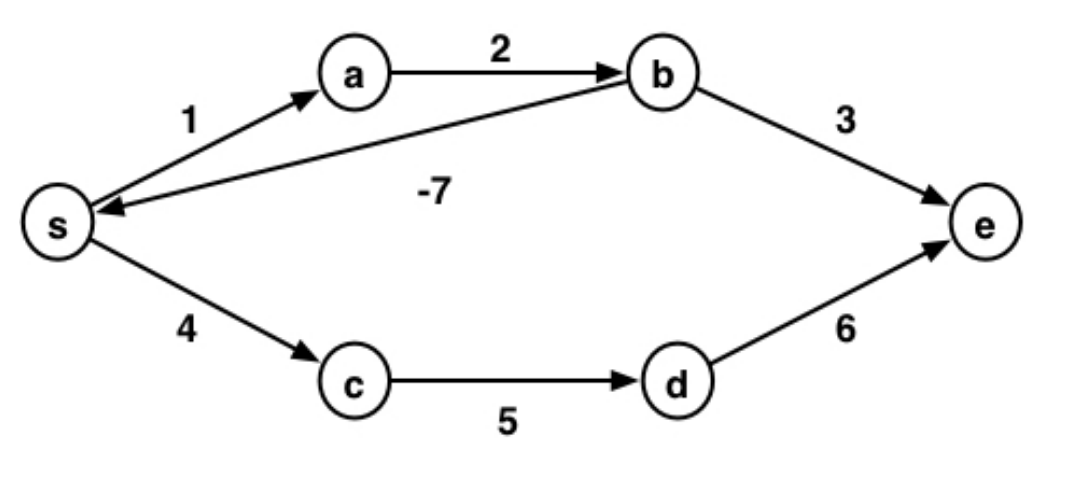

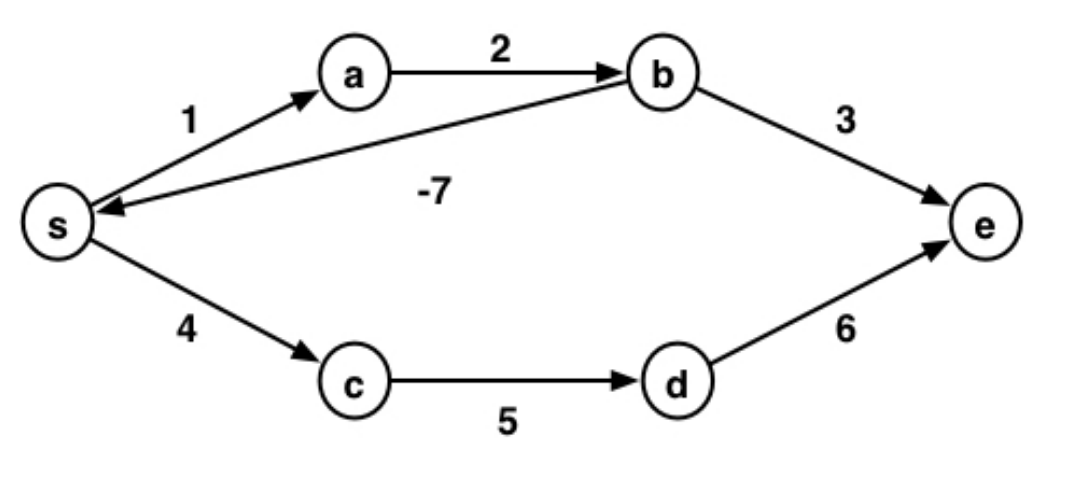

Consider negative cycles: sum of weights in a cycle is less than 0

If there are no negative cycles:

- then the shortest path between any two nodes contains no cycles

- thus, the shortest path has at most $|V|-1$ edges

- compute $\delta^k(u,v)$ from $k=1$ to $k=|V|-1$

If there are negative cycles:

- then the shortest path has weight $-\infty$

- must detect such cycles while computing $\delta^k(u,v)$

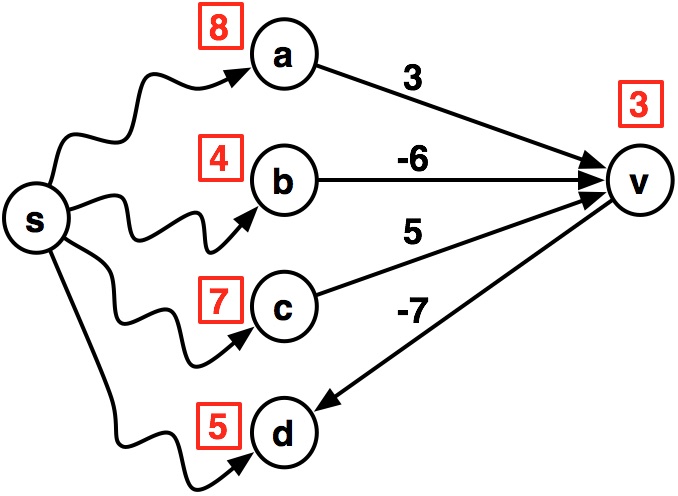

Computing $\delta^{k+1}(u,v)$¶

As usual, we will assume we have recursively computed $\delta^k(s,v)$. To extend this to compute $\delta^{k+1}(s,v)$:

$$ \begin{align} \delta^{k+1}(s, v) = \min&(\delta^{k}(s, v),\\ &\min_{x \in N^-(v)} (\delta^{k}(s, x) + w(x,v)) \end{align} $$where $N^-(v)$ are the in-neighbors of $v$

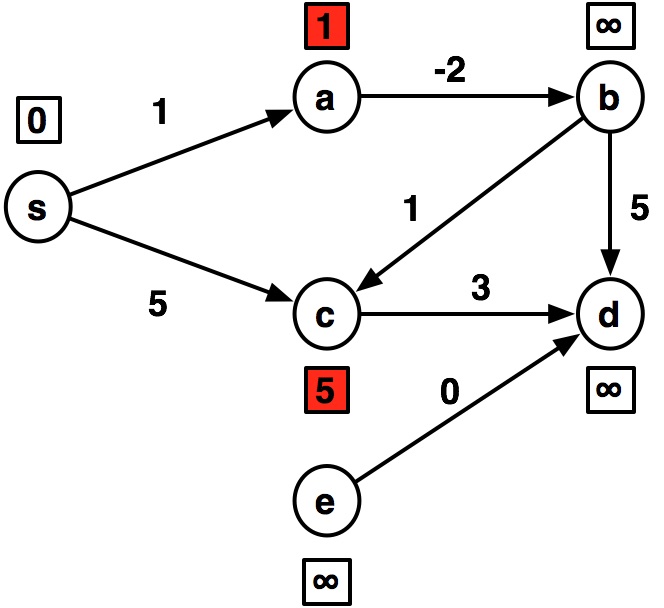

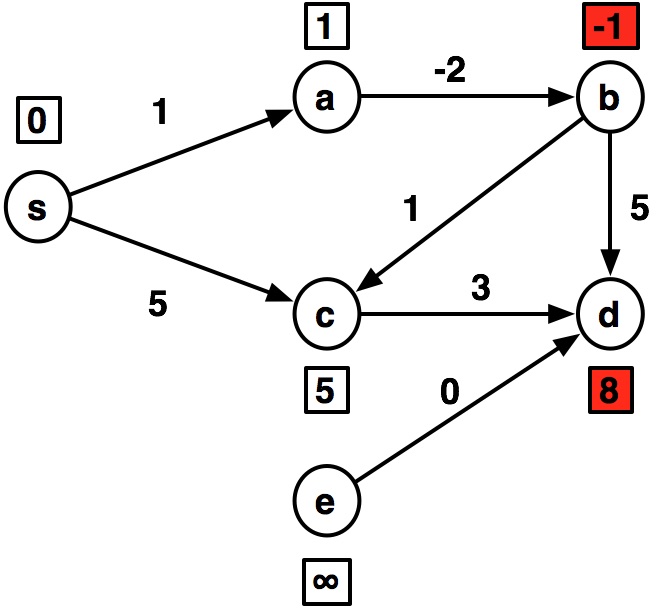

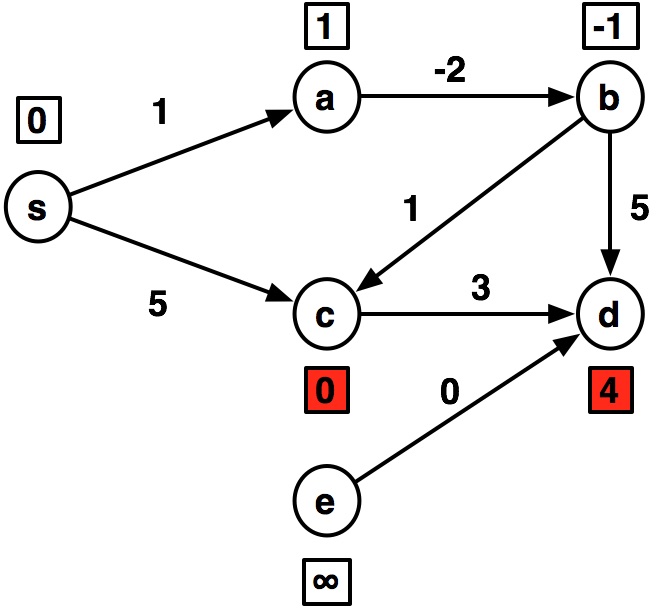

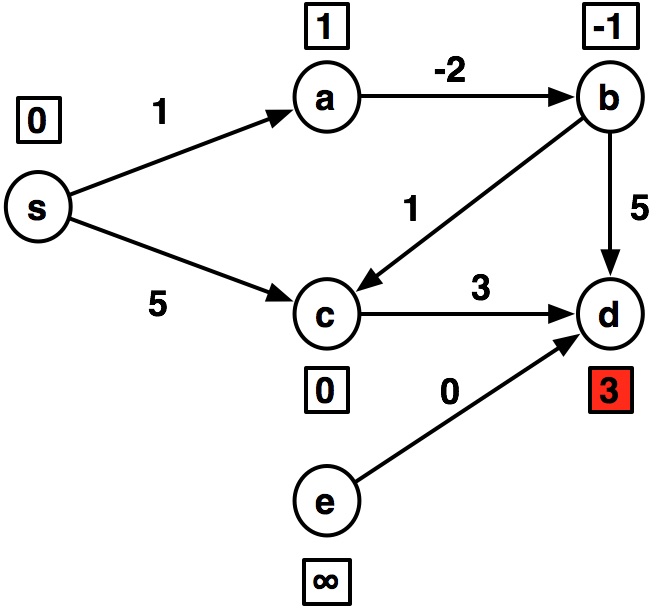

Consider this graph, where we have already computed the shortest paths from the source $s$ to vertices using $k$ or fewer edges.

- Each vertex $u$ is labeled with $\delta^k(s,u)$, its $k$-distance from $s$

- Then, the shortest path to $v$ using at most $k+1$ edges is

Bellman-Ford Algorithm¶

- Initialize: $\delta^0(s,s)=0$ and $\delta^0(s,v)=\infty$ $\forall ~ v \ne s$

- Iterate: Compute $\delta^{k+1}(s,v)$ $\forall v$ as above, using $\delta^{k}(s,v)$ $\forall v$

- We can compute this in parallel for all $v$

When to stop?

Stop when the values converge, that is, when the next iteration makes no updates:

When $\delta^{k+1}(s,v)=\delta^{k}(s,v)$ $~\forall ~~ v$

but: if there are negative cycles, this may never be true.

So, we can instead stop after $|V|$ iterations.

- if we haven't converged at that point, then there must be a negative cycle

Let's look at code and output on this example:

import math

def bellmanford(graph, source):

def bellmanford_helper(distances, k):

if k == len(graph): # negative cycle

return -math.inf

else:

# compute new distances

new_distances = compute_distances(graph, distances)

# check if distances have converged

if converged(distances, new_distances):

return distances

else:

return bellmanford_helper(new_distances, k+1)

# initialize

distances = dict()

for v in graph:

if v == source:

distances[v] = 0

else:

distances[v] = math.inf

return bellmanford_helper(distances, 0)

def compute_distances(graph, distances):

print("\n----")

new_distances = {}

for v, in_neighbors in graph.items(): # this loop can be done in parallel

# compute all possible distances from s->v

v_distances = [distances[v]]

for in_neighbor, weight in in_neighbors:

v_distances.append(distances[in_neighbor] + weight)

new_distances[v] = min(v_distances)

print("{}:{} ".format(v, new_distances[v]), end='')

return new_distances

def converged(old_distances, new_distances):

return old_distances == new_distances

# instead, represent in-neighbors for each node, for constant lookup

graph = {

's': {},

'a': {('s', 1)},# ('c', 0)},

'b': {('a', -2)},

'c': {('s', 5), ('b', 1)},

'd': {('b', 5), ('c', 3), ('e', 0)},

'e': {},

}

# original representation: map from node to out-neighbors

# graph = {

# 's': {('a', 1), ('c', 5)},

# 'a': {('b', -2)},

# 'b': {('c', 1), ('d', 5)},

# 'c': {('d', 3)},

# 'd': {},

# 'e': {('d', 0)}

# }

bellmanford(graph, 's')

---- s:0 a:1 b:inf c:5 d:inf e:inf ---- s:0 a:1 b:-1 c:5 d:8 e:inf ---- s:0 a:1 b:-1 c:0 d:4 e:inf ---- s:0 a:1 b:-1 c:0 d:3 e:inf ---- s:0 a:1 b:-1 c:0 d:3 e:inf

{'s': 0, 'a': 1, 'b': -1, 'c': 0, 'd': 3, 'e': inf}

graph2 = {

's': {},

'a': {('s', 1), ('c', -1)}, # make a negative cycle a->b->c->a, -2

'b': {('a', -2)},

'c': {('s', 5), ('b', 1)},

'd': {('b', 5), ('c', 3)},

'e': {},

}

bellmanford(graph2, 's')

---- s:0 a:1 b:inf c:5 d:inf e:inf ---- s:0 a:1 b:-1 c:5 d:8 e:inf ---- s:0 a:1 b:-1 c:0 d:4 e:inf ---- s:0 a:-1 b:-1 c:0 d:3 e:inf ---- s:0 a:-1 b:-3 c:0 d:3 e:inf ---- s:0 a:-1 b:-3 c:-2 d:2 e:inf

-inf

Cost of Bellman-Ford¶

def compute_distances(graph, distances):

new_distances = {}

for v, in_neighbors in graph.items(): # this loop can be done in parallel

v_distances = [distances[v]]

for in_neighbor, weight in in_neighbors:

v_distances.append(distances[in_neighbor] + weight)

new_distances[v] = min(v_distances)

return new_distances

Work

- For each vertex, we loop through all of its in-neighbors.

- We then take the minimum over its in-neighbors

- Thus, we will visit each edge in the graph once in each iteration of the algorithm ($|E|$)

- There are at most $|V|$ iterations of the algorithm, to the total work for

compute_distancesis $O(|V| \cdot |E|)$.

def compute_distances(graph, distances):

new_distances = {}

for v, in_neighbors in graph.items(): # this loop can be done in parallel

v_distances = [distances[v]]

for in_neighbor, weight in in_neighbors: # Can be done in O(1) span

v_distances.append(distances[in_neighbor] + weight)

new_distances[v] = min(v_distances) # Can be done in O(lg n) span

return new_distances

Span

- Because we can do the outer loop in parallel, we must consider the maximum span of any vertex $v$.

- In the worst case, $v$ can have $|V|-1$ in-neighbors. The

minoperation will then take $O(\lg |V|)$ span, assuming we usereduceto implement it. - Thus, each iteration has $O(\lg |V|)$ span, and we have at worst $|V|$ iterations, run sequentially, resulting in total span of $O(|V| \lg |V|)$.

What about the work to check if we have converged?

def converged(old_distances, new_distances):

return old_distances == new_distances

Under the hood:

def converged(old_distances, new_distances):

for k in old_distances:

if old_distances[k] != new_distances[k]:

return False

return True

This is $O(|V|)$

But, if we were more clever, we could include this check inside the compute_distances function, just before assigning the new_distances value.

...

min_v = min(v_distances)

if min_v != new_distances[v]:

converged=False

new_distances[v] = min(v_distances)

...

so, we don't incur any additional cost for this check.

Final work/span of Bellman-Ford¶

Work: $O(|V| \cdot |E|)$

Span: $O(|V| \lg |V|)$

compare with:

Dijkstra:

$~~~$ Work $O(|E|\log |V|)$

$~~~$ Span $O(|E|\log |V|)$

BFS:

$~~~$ Work $O(|E|+ |V|)$

$~~~$ Span $O(|E| + |V|)$

So, we can see we pay significant costs going from unweighted $\rightarrow$ weighted-positive $\rightarrow$ weighted-negative graphs.

- Although, consider the difference in span between Dijkstra and Bellman-Ford

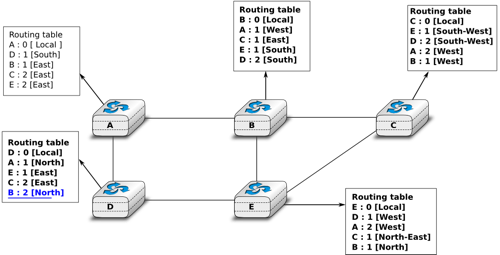

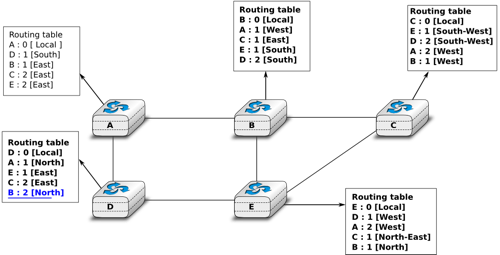

Bellman-Ford is used in network routing:

- Each router has a routing table containing the shortest path from source to destination

- Edge weights account for latency between routers.

- But, no router has perfect knowledge of the network.

- Routers exchange information in a peer-to-peer fashion to update routing tables.

- But wait, there can't be a negative weight in this graph! (no "negative latency").

- So, why use Bellman-Ford instead of Dijkstra?

- Bellman-Ford is naturally a distributed/concurrent algorithm -- each node updates its shortest paths and exchanges with neighbors.

- Dijkstra requires each node to have perfect knowledge of the network, in order to make the optimal, greedy step at each iteration.