Today's agenda:

- Optimizing Binary Search Trees using Dynamic Programming

Optimal Binary Search Trees¶

For a set of keys $S$ ($|S|=n$), a binary search tree organizes $S$ as follows. Each element $x$ of $S$ is placed in the tree so that all elements $y \leq x$ are in the left subtree of $x$ and all of the elements $z>x$ are in the right subtree. For any binary tree $T$, let $d(x, T)$ be the depth of an element $x\in S.$

A balanced binary search tree has the property that the maximum depth is $O(\log n)$. There are a number of approaches to ensure that search, insertion and deletion operations can be performed in $O(\log n)$ time.

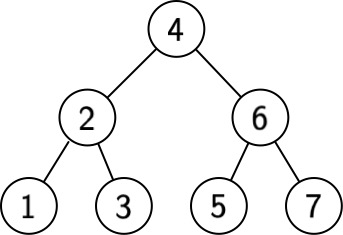

Example: Let $S = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7\}$. Then a balanced binary search tree $T$ would have the following structure:

Suppose we are focused on the cost of retrieval of items from $T$. In the worst case, retrieval has cost $3$.

But what if we knew the frequency of retrieval $f(x)$ for each $x\in S$? We previously used this additional knowledge to greatly improve compression. Then a binary search tree $T$ above has search cost $C(T) = \sum_{x\in S} f(x)\cdot d(x, T).$

Do frequencies affect the best retrieval cost we can achieve?

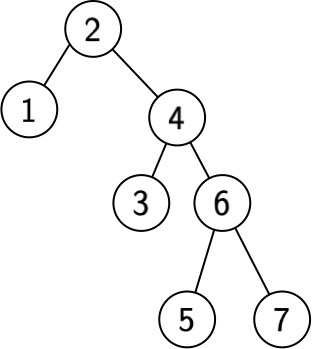

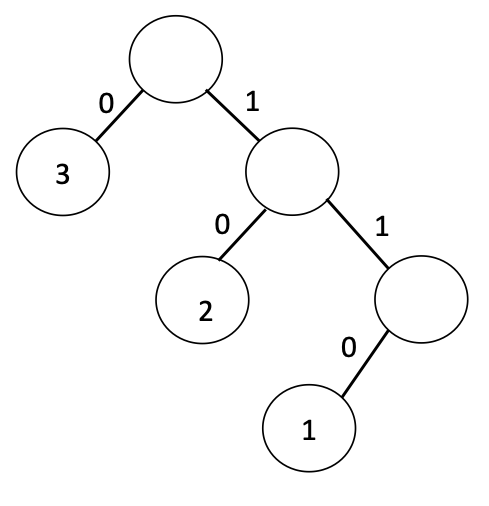

Example: Let $f(1) = 1000, f(2) = 1, f(3) = 1, f(4) = 1, f(5) = 1, f(6) = 1, f(7) = 1.$ Then a balanced tree has cost $1+ 4 + 9 + 3000 = 3014.$ But consider the following tree:

The cost is $1 + 2000 + 2 + 6 + 8 = 2017$, which is much better!

With the given frequencies, does this binary search tree minimize retrieval cost?

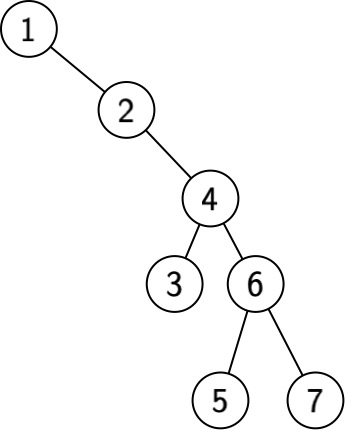

No! Here is a better tree with cost $1000 + 2 + 3 + 8 + 10 = 1023$:

Given a set of $S$ comparable elements with given frequencies, the Optimal Binary Search Tree problem asks us to find the binary search tree $T$ for $S$ that minimizes

$$C(T) = \sum_{x\in S} f(x)\cdot d(x, T).$$Would a greedy algorithm work? What if we simply made the most frequent item the root?

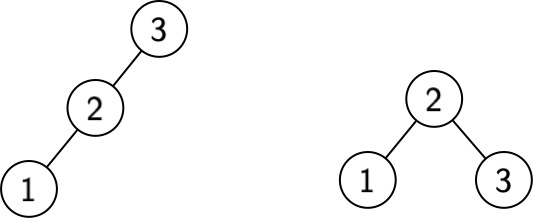

This approach fails if the largest element is most frequent. Consider $S={1, 2, 3}$ where $f(1) = 9, f(2)=9, f(3) = 10$.

A greedily constructed tree has $3$ as the root and cost $10+18+29 = 55.$ A balanced tree has $2$ as the root and cost $9 + 18 + 20 = 47.$

Why is this different from Huffman coding?

A Dynamic Programming Approach¶

Suppose we have the elements of $S$ in sorted order. Let $S_{i,j}$ denote the elements from rank $i$ to rank $j$ inclusive. For any $T$ with root $S_r$, let's look at its cost in terms of the left and right subtrees $T_L$ and $T_R$:

$\begin{align} C(T) &=& \sum_{x\in T} f(x)\cdot d(x, T) \\ &=& f(S_r) + \sum_{x\in T_L} f(x) \cdot (d(x, T_L) + 1) + \sum_{x\in T_R} f(x) \cdot (d(x, T_R) + 1) \\ &=& f(S_r) + \sum_{x\in T_L} f(x) + \sum_{x\in T_L} f(x) \cdot d(x, T_L) + \sum_{x\in T_R} f(x)+ \sum_{x\in T_R} f(x) \cdot d(x, T_R) \\ &=& \sum_{x\in T} f(x) + \sum_{x\in T_L} f(x) \cdot d(x, T_L) + \sum_{x\in T_R} f(x) \cdot d(x, T_R) \\ &...& \mathit{Note: } ~~ \sum_{x\in T} f(x) = f(S_r) + \sum_{x\in T_L} f(x) + \sum_{x\in T_R} f(x) \\ &=& \sum_{x\in T} f(x) + C(T_L) + C(T_R) \\ \end{align}$

Let $\mathit{OBST}(S)$ be the cost of an optimal binary search tree for $S$ with given frequencies. Some element $r$ in $S$ must be the root of an optimal binary search tree. Moreover, the left and right subtrees must also be optimal binary search trees for $S_{0,r-1}$ and $S_{r+1, n-1}$, respectively.

But which element $r$ should be the root?

It should be the element that yields left and right subtrees so that the overall tree $T$ minimizes the total cost $C(T)$.

Optimal Substructure for Optimal Binary Search Trees: For a set of $n$ keys $S$,

$$ \mathit{OBST}(S) = \begin{cases} 0,~~~\text{if}~~ |S| = 0\\ \sum_{x \in S} f(x) + \min_{i \in [n]} \left(\mathit{OBST}(S_{1,i-1})+\mathit{OBST}(S_{i+1,n-1})\right),~~~\text{otherwise}\\ \end{cases} $$Yet again we see that the recursion tree for this optimal substructure property grows exponentially. Similar to the longest increasing subsequence problem, the evaluation of subproblems requires time linear in the size of the subproblem.

The total number of subproblems is simply the total number of contiguous subsequences, which is $O(n^2)$. Thus the total work required is $O(n^3)$.

If we examine the recursion DAG, we can see that the longest path is of length $n$ (we reduce the size of the subproblems by at least one in each recursion). Since we can compute the required minimum in parallel, the span at each vertex in the DAG is $O(\log n)$ for a total span of $O(n\log n)$.

This completes our discussion of dynamic programming as a paradigm.

We will move on to discuss graphs in the next two modules, where we will a variety of our algorithmic paradigms in action.