Agenda:

- Quicksort

Sorting¶

We saw how the problem of selection could be solved with a randomized algorithm. The key was to choose a random element and then partition the list into two parts.

What if we recursively sorted these two parts?

Let $a=\langle 2, 5, 4, 1, 3, -1, 99\rangle.$

Suppose we chose 4 as the pivot.

Then the two parts of the list are $\ell=\langle 2, 1, 3, -1\rangle$ and $r=\langle 5, 99\rangle$.

In sorted order they are $\ell'=\langle -1, 1, 2, 3\rangle$ and $r'=\langle 5, 99\rangle$.

So all we have to do is append $l'$, the pivot and $r'$!

This suggests a divide-and-conquer algorithm, but with similar characteristics as our algorithm for selection.

This sorting algorithm is actually called Quicksort (invented in 1959 by C. A. R. Hoare).

In terms of parallelism, we can partition in parallel as before and sort the two parts of the list in parallel.

Analysis¶

How should we analyze the work of quicksort?

We'll take a slightly different approach than for selection to estimate the expected work. To account for work, we'll look at the total amount of expected work.

First, an assumption to streamline our analysis:

We will "simulate" randomess using priorities: before the start of the algorithm, we assign each key a uniformly random priority from the real interval $[0, 1]$ such that each key has a unique priority. The algorithm then picks the pivot by selecting the key with the highest priority.

Let the random variable $Y(n)$ be the number of comparisons made by Quicksort on an input of size $n$. Note that the work is $O(Y(n))$, since there is $O(1)$ work done by non-comparisons (i.e., choosing pivots, concatenation of lists).

We ultimately want to know how many comparisons are made by quick sort.

Quantifying the number of expected comparisons¶

Let $X_{ij}$ be an indicator random variable that is 1 if $t_i$ and $t_j$ are ever compared and 0 otherwise. So we have that $Y(n) = \sum_i \sum_j X_{ij}$ and so this means that:

We have that $\mathbf{E}[X_{ij}] = \mathbf{P}[X_{ij} = 1]$.

So when are a pair of elements $t_i$ and $t_j$ compared?

When are a pair of elements $t_i$ and $t_j$ compared?¶

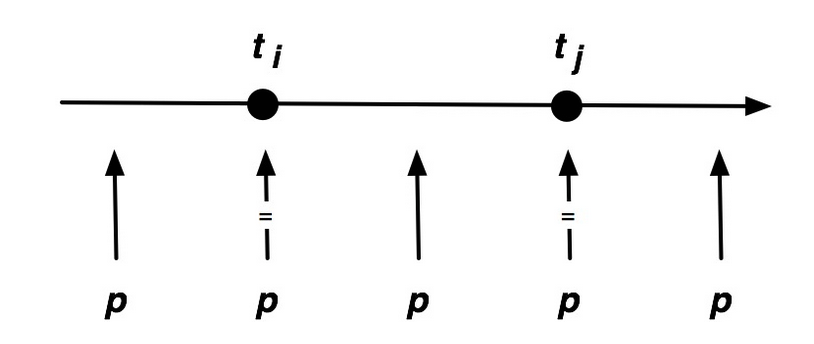

It's useful to consider the sorted version of $a$, indexed as $t_0, t_1, \ldots, t_{n-1}$.

e.g.

$ a = [1,~~~~\mathbf{2},~~~~5,~~~~6,~~~~9,~~~\mathbf{10},~~~~12] \\ p = [0.3, ~0.2, ~0.7, ~0.8, ~0.4, ~0.1, ~0.5] $

If any element between $t_i$ and $t_j$ in the sorted order is chosen as a pivot before $t_i$ or $t_j$, then they will never be compared.

E.g, two elements $t_i$ and $t_j$ are only ever compared if one of them is a pivot and if it has the highest priority in the sequence of elements $t_i$ to $t_j$.

Since the pivot is chosen randomly, the probability that either $t_i$ or $t_j$ has the highest probability in the range of elements from $t_i$ to $t_j$ is:

$$ \mathbf{P}[X_{ij}] = \frac{2}{j - i + 1}. $$$j - i +1$ is the number of elements between $t_i$ and $t_j$ inlcuding $t_i$ and $t_j$.

$

a = [1,~~~~\mathbf{2},~~~~5,~~~~6,~~~~9,~~~\mathbf{10},~~~~12] \\

p = [0.3, ~0.2, ~0.7, ~0.8, ~0.4, ~0.1, ~0.5]\\

i = ~[0, ~~~\mathbf{1}, ~~~~~2, ~~~~3, ~~~~4, ~~~~\mathbf{5}, ~~~~~6]

$

Expected Work¶

$$\begin{align} \mathbf{E}\left[{Y(n)}\right] &\leq \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \sum_{j=i+1}^{n} \mathbf{E}\left[{X_{ij}}\right] \\ &= \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \sum_{j=i+1}^{n} \frac{2}{j-i+1} \\ &= \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \sum_{k=1}^{n-i} \frac{2}{k+1} \\ &= \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \sum_{k=1}^{n} \frac{2}{k} \\ &\leq 2 \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \ln n ~~~~~~~~~ \hbox{Harmonic series:} \sum_{k=1}^n \frac{1}{k} < \ln n \\ &= O(n\lg n) \end{align}$$Span¶

Analyzing the span of Quicksort can be done in the same way as we did for selection.

That is, if we have a guarantee that at level $d$ of recursion that the larger of the two lists is $(3/4)^d n$, then we can show that the span at each level is $O(\log n)$ (expected).

Using the same approach as for selection we can show that the total span is $O(\log^2 n)$ with high probability.