Agenda:

- Divide-and-Conquer with

reduce - Maximum Contiguous Subsequence Sum

- Euclidean TSP

Recall that we gave a divide-and-conquer algorithm for reduce:

$reduce \: f \: id \: a = \begin{cases} id & \hbox{if} \: |a| = 0\\ a[0] & \hbox{if} \: |a| = 1\\ f(reduce \: f \: id \: (a[0 \ldots \lfloor \frac{|a|}{2} \rfloor - 1]), \\ \:\:\:reduce \: f \: id \: (a[\lfloor \frac{|a|}{2} \rfloor \ldots |a|-1])& \hbox{otherwise} \end{cases} $

For example:

reduce(merge, [], list(map(singleton, [1,3,6,4,8,7,5,2])))

Can all divide-and-conquer algorithms be implemented with reduce?

The divide-and-conquer framework is more general than reduce.

reduce cannot be used when, for example, we wish to split the input into 3 or more parts, or if they are of unequal size.

Maximum Continguous Subsequence Sum¶

Given a sequence of integers, the Maximum Contiguous Subsequence Sum Problem (MCSS) requires finding a contiguous subsequence with maximum total sum:

E.g,

For $a = \langle 1, -2, 0, 3, -1, 0, 2, -3 \rangle$ a maximum contiguous subsequence (MCS) is $\langle\, 3, -1, 0, 2 \rangle$. Another is $\langle 0, 3, -1, 0, 2 \rangle.$

We define the sum of an empty sequence to $-\infty$.

MCSS is useful for many applications, from genomics to data science and finance.

Brute Force¶

Let's first take a brute-force approach to this problem. What is the solution space, and how long does it take to evaluate it?

- Consider every contiguous subsequence and evaluate the sum of each.

- There are $O(n^2)$ contiguous subsequences.

- To evaluate the sum of each contiguous subsequence we need $O(n)$ work and $O(\log n)$ span.

- Thus the brute-force approach takes $O(n^3)$ work and $O(\log n)$ span.

Can we do better using divide-and-conquer?

Divide and Conquer¶

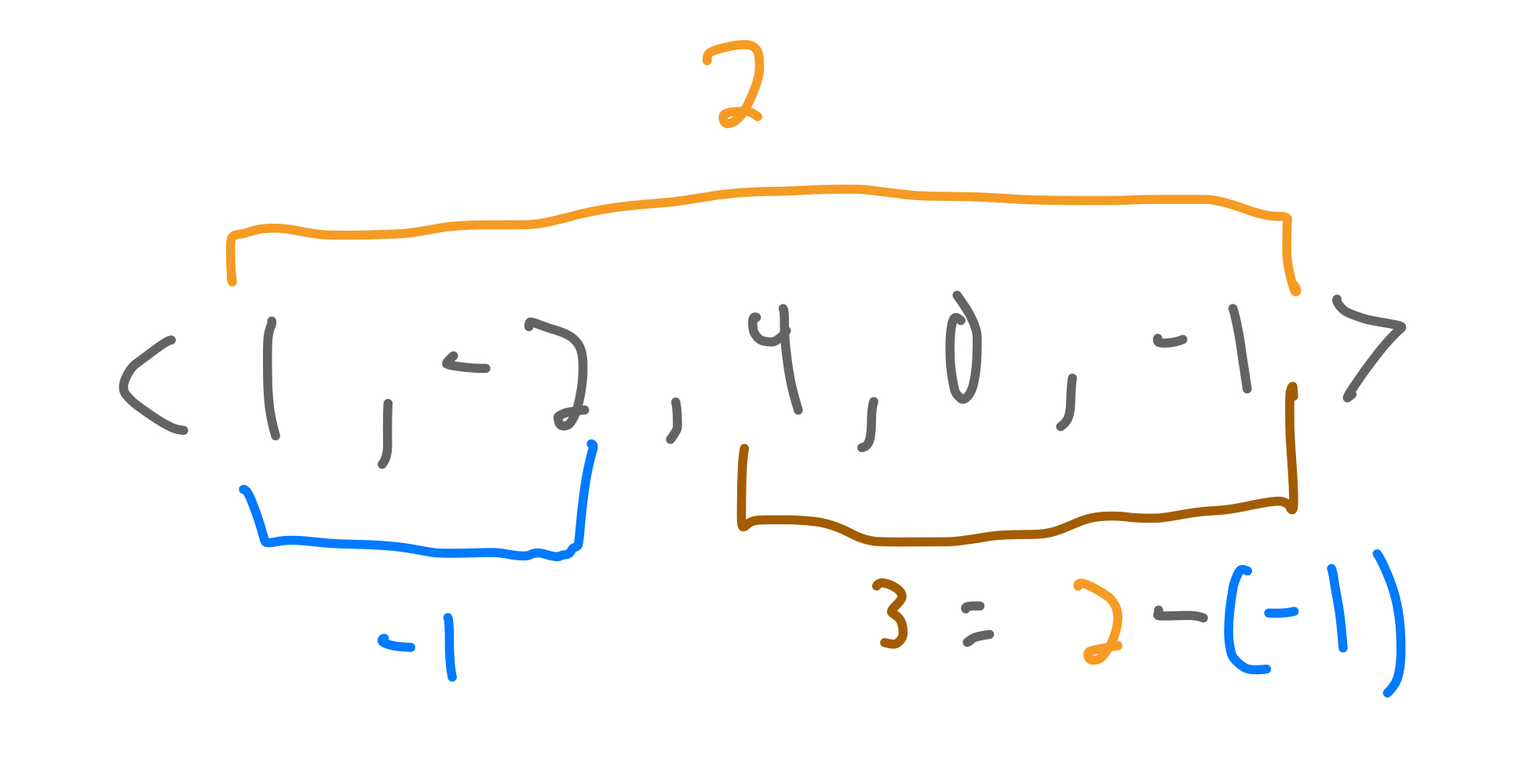

$$a = \langle 1, -2, 0, 3, -1, 0, 2, -3 \rangle$$$$\texttt{MCS} = \langle\, 0, 3, -1, 0, 2 \rangle$$$$\texttt{MCSS} = 4$$As usual let's start by dividing the input into two equal parts and recursively finding the solution.

If the $\texttt{MCSS}$ is within either part entirely, then in the combine step we just need to return the sum.

But what if the $\texttt{MCS}$ spans the two halves?

Example: $a = \langle 1, -2, 0, 3, -1, 0, 2, -3 \rangle$

- Split into left = $\langle 1, -2, 0, 3 \rangle$, right = $\langle -1, 0, 2, -3 \rangle$

- Left $\texttt{MCSS}$ comes from $\langle 0, 3 \rangle$ (or just $\langle 3 \rangle$) $= 3$

- Right $\texttt{MCSS}$ comes from $\langle 0, 2 \rangle$ $= 2$

- But, the best $\texttt{MCSS}$ crossing the cut comes from $\langle 0, 3, -1, 0, 2 \rangle$ $=4$

Spanning the Middle¶

The maximum sum spanning the cut is the sum of the largest suffix on the left plus the largest prefix on the right.

E.g,

$$\langle 1, -2, 0, 3, -1, 0, 2, -3 \rangle$$$$\langle 1, -2, \pmb{\underline{0, 3}} \rangle ~~ \langle \pmb{\underline{-1, 0, 2}}, -3 \rangle$$If we could identify the $\texttt{MCSS}$ ending at position $\lfloor n/2 \rfloor - 1$ and the $\texttt{MCSS}$ beginning at position $\lfloor n/2 \rfloor$, then we could add values of these to obtain a candidate $\texttt{MCSS}$ for the whole sequence.

Then the best of the three candidate solutions is an $\texttt{MCSS}$ for the entire sequence:

- $\texttt{MCSS(left)}$

- $\texttt{MCSS(right)}$

- $\texttt{bestAcross(left, right)}$

- $\texttt{MCSS-suffix}$: maximum contiguous sum ending at last element

- $\texttt{MCSS-prefix}$: maximum contiguous sum starting at first element

Divide and Conquer Algorithm¶

Suppose we have $\texttt{MCSS-suffix}$ and $\texttt{MCSS-prefix}$ and $\mathit{bestAcross}~(b, c)$ which constructs an $\texttt{MCSS}$ crossing the split using these solutions. Then we could give this divide-and-conquer algorithm:

Correctness:

We can proceed by induction as usual. The base case produces the correct results. The $\texttt{MCSS}$ of an empty list is $-\infty$ and the $\texttt{MCSS}$ of a list of size $1$ is its single element.

For the induction step, we make the hypothesis that the recursively computed MCSS's for $b$ and $c$ are correct. With a correct implementation of $\mathit{bestAcross}$ (we will detail this function soon), we can conclude $\max\{m_b, m_c, m_{bc}\}$ is an MCSS.

Work/Span:

We will show that $\texttt{MCSS-suffix}$ and $\texttt{MCSS-prefix}$ can be solved in $\Theta(n)$ work and $\Theta(\log n)$ span.

Using this assumption about $\mathit{bestAcross}$ we have that:

and

$$ S(n) = S(n/2) + \Theta(\log n)$$These yield $O(n\log n)$ work and $O(\log^2 n)$ span.

Implementing $\texttt{MCSS-suffix}$ and $\texttt{MCSS-prefix}$¶

How do we obtain an $\texttt{MCSS}$ starting at a specified position ($\texttt{MCSS-prefix}$) or ending at a specified position ($\texttt{MCSS-suffix}$)?

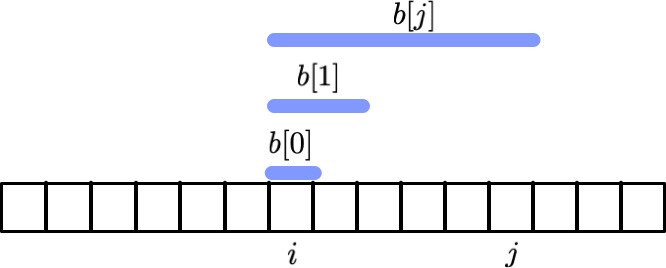

$\texttt{MCSS-prefix}$ Intuition

Since we are calculating the sum from the start of a sequence, we can use prefix sum to solve it.

$\texttt{MCSS-prefix}$ Intuition

Since we are calculating the sum from the start of a sequence, we can use prefix sum to solve it.

left = $\langle 1, -2, 0, 3 \rangle$, right = $\langle -1, 0, 2, -3 \rangle$

>>> scan(add, 0, [-1,0,2,-3])

([-1, -1, 1, -2], -2)

The max of the prefixes gives us the $\texttt{MCSS}$ starting at the beginning of $\texttt{right}$.

Max of $1$ happens when using prefix $[-1, 0, 2]$

$\texttt{MCSS}$ starting at position $i$:

$$ \begin{array}{l} \mathit{MCSSprefix}~a~i = \\ ~~~~\texttt{let} \\ ~~~~~~~~b = \mathit{scan}~\,{\texttt{+}}\,~0~a~[i \cdots (|a|-1)] \\ ~~~~\texttt{in} \\ ~~~~~~~~\mathit{reduce}~\mathit{max}~{-\infty}{}~b \\ ~~~~\texttt{end} \end{array} $$Runtime

$\texttt{scan}$, $\texttt{reduce}$

$W(n) \in \Theta(n)$

$S(n) \in \Theta(\lg n)$

$\texttt{MCSS-prefix}$

$W(n) \in \Theta(n)$

$S(n) \in \Theta(\lg n)$

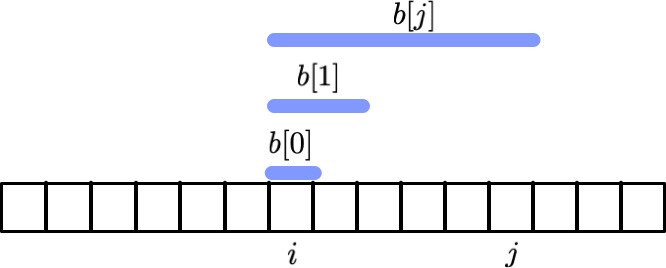

$\texttt{MCSS-suffix}$ Intuition:

We can calculate suffix sums by subtracting prefix sums from the sum of the entire sequence.

Subtracting the smallest prefix sum will give the max suffix sum.

>>> prefixes, sum = scan(add, 0, [1,-2,0,3])

>>> print('prefixes =', b, 'sum =', v)

prefixes = [1, -1, -1, 2] sum = 2

>>> min_prefix = reduce(min, -math.inf, prefixes)

>>> print('min_prefix =', w)

min_prefix = -1

>>> print('suffix_sum =', sum - min_prefix)

suffix_sum = 3

Runtime

$\texttt{MCSS-suffix}$

$W(n) \in \Theta(n)$

$S(n) \in \Theta(\lg n)$

def MCSS_prefix(a):

# return the MCSS in a that starts at index i

b = scan(add, 0, a)

return reduce(max, -math.inf, b[0])

def MCSS_suffix(a):

# return the MCSS in a that ends at index j

b = scan(add, 0, a)

m = reduce(min, -math.inf, b[0])

return b[1] - m

def best_across(b, c):

# return the MCSS of a sequence that crosses input sequences b and c

return MCSS_suffix(b) + MCSS_prefix(c)

def MCSS(a):

if len(a) == 0:

return -math.inf

elif len(a) == 1:

return a[0]

else:

b = a[:len(a)//2]

c = a[len(a)//2:]

sum_b = MCSS(b)

sum_c = MCSS(c)

sum_across = best_across(b,c)

return max(sum_b, sum_c, sum_across)

left = [1,-2,0,3]

right = [-1,0,2,-3]

MCSS(left + right)

4

Traveling Salesperson Problem¶

Consider a slight variant of the MST problem:

Given a graph $G=(V,E)$, find a tour that visits each node exactly once and then returns to the origin node.

- every node is visited

- no edges are repeated

The Euclidean Traveling Salesperson Problem (eTSP)¶

In eTSP, you are given a set of $n$ 2D points.

The goal is to find a "tour" of the points with minimum cost.

That is, we must construct a sequence of all the points (i.e., a sequence of 2D points) that begins and ends with the same point such that:

- every point is visited exactly once (except the starting point)

- the sum of distances between adjacent points is minimized

This is an incredibly widespread and useful problem -- consider all the various kinds of routing problems (Amazon, USPS, UPS, etc.) that are solved every day.

Which solution is better?

Brute-Force?¶

Given an input with $n$ points, how many possible solutions are there?

What is the solution space and how can we search it?

There are $n!$ possible solutions, and we must check the cost of each by summing $n-1$ distances.

This can be done with $O(n)$ work and $O(\lg n)$ span using $\texttt{reduce}$.

What is the runtime of brute force eTSP?

$O(n\cdot n!)$ work and $O(\log n)$ span.

This is good span, but an astronomical amount of work. What if we had more points?

16! is about $2 x 10^{13}$, so while there are very few points the brute-force approach is not tractable!

Divide-and-Conquer?¶

What intuition can we get about the fact that this problem is in 2D?

Since clusters of points can possibly be dealt with separately, how about a divide-and-conquer approach?

Divide and Conquer Approach¶

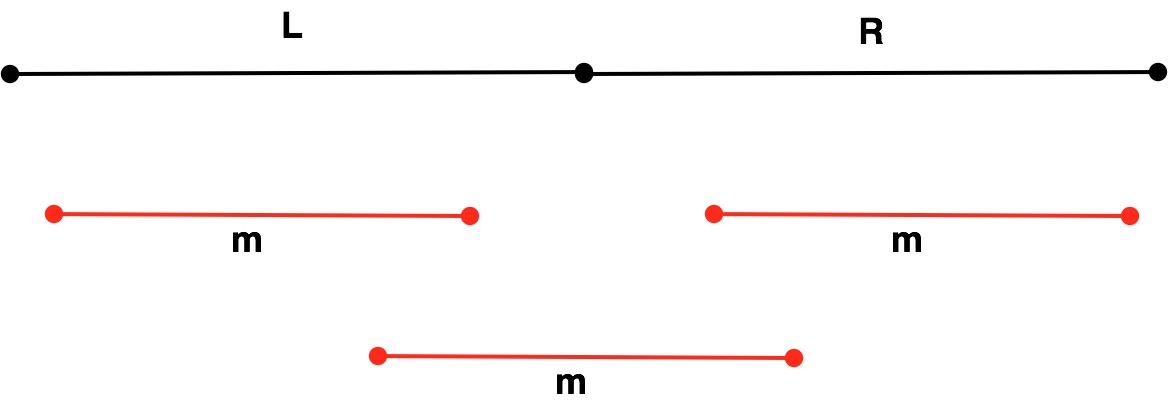

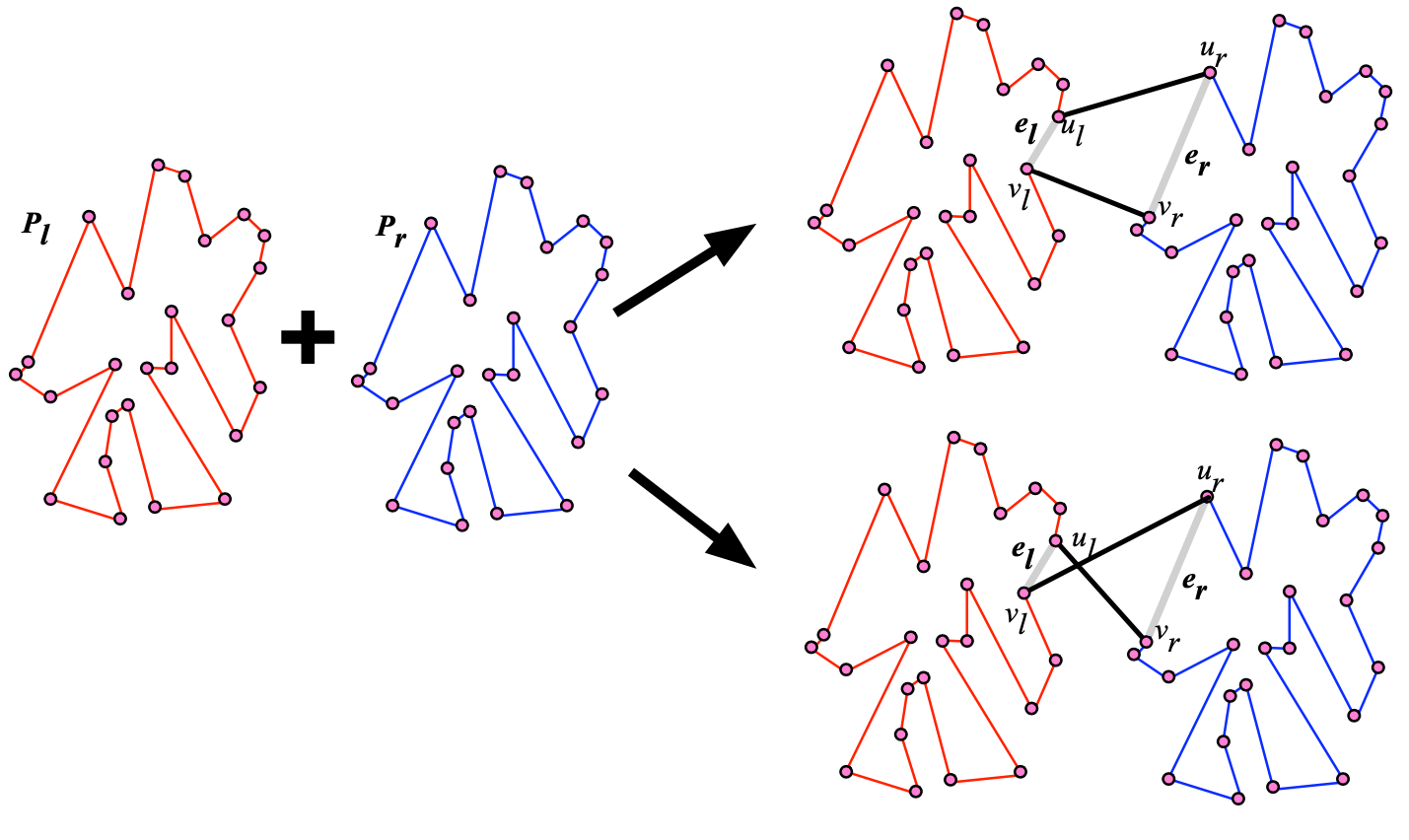

We can split the input using a "cut" through the plane that separates the input points into two equal parts. Then, recursively solve eTSP for each smaller point set.

How do we combine smaller solutions into larger ones?

Combining eTSP tours¶

We need to make sure that two tours can be combined into the best possible single tour.

To do this, we try all possible pairs of edges across both sides and pick the pair which when connected gives the minimum cost. This yields the following algorithm.

The function $\mathit{minVal}_{\mathit{first}}$ iterates over all pairs of edges and finds the pair yielding the minimum cost.

The function $\mathit{swapEdges}(E,e,e')$ swaps the end points of edges $e$ and $e'$. As there are two ways to swap, it picks the cheaper one.

Correctness¶

Does this algorithm compute a tour? Does this algorithm compute a minimum-cost tour?

We can show by induction that this algorithm always produces a tour.

However, the combine step does not necessarily produce a minimum cost tour!¶

Our algorithm is actually not correct in the sense that it does not necessarily return the optimal solution. Rather, it is a heuristic that works well in practice.

Actually, we currently do not know of any polynomial-work algorithm to solve this problem.

In fact, the brute-force algorithm is essentially the best we can do. (We'll get to this in more detail at the end of the semester.)

It is possible to efficiently is to compute an approximation to the optimal eTSP solution. It is possible to compute a solution that is within $(1+\epsilon)$ of optimal. The running time is polynomial in $n$ and $1/\epsilon$.

Work/Span:

This algorithm has two recursive calls that each operate on $n/2$ points.

Our combination step requires that we check $O(n^2)$ ways too cross the cut and compute the best. This requires $O(n^2)$ work and $O(\log n)$ span.

So we have that the work is $W(n) = 2W(n/2) + O(n^2).$ This is a root-dominated recurrence, and thus $W(n) = O(n^2)$.

The span is $S(n) = S(n/2) + O(\log n)$. This is a balanced recurrence with $\lg n$ levels, and so $S(n) = O(\log^2 n)$.