Scan¶

reduce doesn't store the intermediate results, which limits it somewhat.

scan is like reduce, but it keeps track of the intermediate computations (like iterate does).

$scan \: (f : \alpha \times \alpha \rightarrow \alpha) (id : \alpha) (a : \mathbb{S}_\alpha) : (S_\alpha * \alpha)$

Input is:

- $f$: an associative binary function

- $a$ is the sequence

- $id$ is the left identity of $f$ $\:\: \equiv \:\:$ $f(id, x) = x$ for all $x \in \alpha$

Returns:

- a tuple containing:

- a value of type $S_\alpha$, the sequence of intermediate values

- a value of type $\alpha$ that is the result of the "sum" with respect to $f$ of the input sequence $a$

$scan \: f \: id \: a = (\langle reduce \:\: f \:\: id \:\: a[0 \ldots (i-1)] : 0 \le i < |a| \rangle,$

$\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\: reduce \:\: f \:\: id \:\: a)$

def reduce(f, id_, a):

if len(a) == 0:

return id_

elif len(a) == 1:

return a[0]

else:

# can call these in parallel

return f(reduce(f, id_, a[:len(a)//2]),

reduce(f, id_, a[len(a)//2:]))

def add(x, y):

return x + y

def scan(f, id_, a):

"""

This is a horribly inefficient implementation of scan

only to understand what it does.

We'll discuss how to make it more efficient later.

"""

return (

[reduce(f, id_, a[:i+1]) for i in range(len(a))],

reduce(f, id_, a)

)

scan(add, 0, [2,1,3,2,2,5,4,1])

([2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 15, 19, 20], 20)

scan is sometimes called prefix sum, as in the previous example it computes the sum of every prefix of a list.

# what does this do?

import math

def gt(x,y):

return x if x > y else y

scan(gt, -math.inf, [10,4,5,12,3,16,5])

([10, 10, 10, 12, 12, 16, 16], 16)

e.g., recall Rightmost Positive

Given a sequence of integers $a$, for each element in $a$ find the rightmost positive number to its left.

E.g.,

$rpos \: \langle 1, 0, -1, 2, 3, 0, -5, 7 \rangle \Rightarrow \langle -\infty, 1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3 \rangle$

We solved with iterate, but we can also solve with scan.

def select_positive(last_positive_value, next_element):

"""

Params:

last_positive_value...the last positive value seen

next_element..........next element from input list

Returns:

the element to be remembered going forward

"""

if next_element > 0: # remember this new value

return next_element

else: # reuse the old value

return last_positive_value

scan(select_positive, -math.inf, [1,0,-1,2,3,0,-5,7])

([1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3, 7], 7)

But, because our scan implementation is currently slow, this doesn't gain us anything.

Surprisingly, we can reduce the work and span of scan, even though it looks "hopelessly serial."

def scan(f, id_, a):

"""

This is a horribly inefficient implementation of scan

only to understand what it does.

We'll discuss how to make it more efficient later.

"""

return (

[reduce(f, id_, a[:i+1]) for i in range(len(a))],

reduce(f, id_, a)

)

Improving Scan¶

We will look at how to improve scan approach using prefix_sum as an example.

$\texttt{prefix_sum}([2,1,3,2,2,5,4,1]) \rightarrow ([0, 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 15, 19], 20)$

Divide and conquer won't quite work...why?

need sum at $i-1$ to compute sum at $i$

Instead, we use an idea called contraction that is like divide and conquer, but doesn't require subproblems to be independent. Yet it still allows some parallelism.

Key observation:

Given input $[2,1,3,2,2,5,4,1]$ we can compute pairwise addition on each adjacent pairs of numbers:

$[2,1,3,2,2,5,4,1] \rightarrow$

$[(2+1), (3+2), (2+5), (4+1)] \rightarrow$

$[3, 5, 7, 5]$

These four additions can be done in parallel.

Contraction:

$[2,1,3,2,2,5,4,1] \rightarrow [(2+1), (3+2), (2+5), (4+1)] \rightarrow \pmb{[3, 5, 7, 5]}$

This is a partial output. How do we modify this to get the final output?

If we run prefix sum on this, we get:

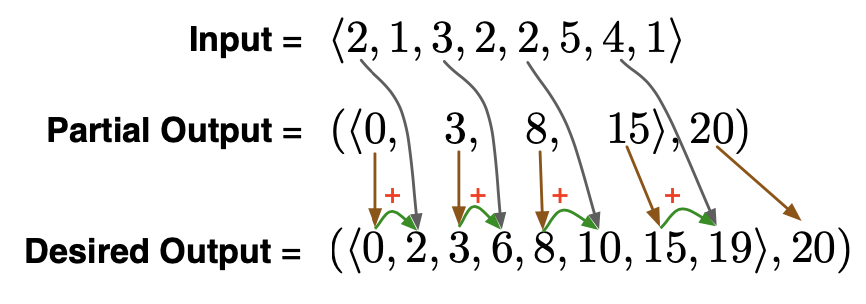

$\texttt{prefix_sum}([3, 5, 7, 5]) \rightarrow ([0, 3, 8, 15], 20)$

We want to end up with:

$\texttt{prefix_sum}([2,1,3,2,2,5,4,1]) \rightarrow ([\mathbf{0}, 2, \mathbf{3}, 6, \mathbf{8}, 10, \mathbf{15}, 19], 20)$

How can we combine this partial solution with the original input $[2,1,3,2,2,5,4,1]$ to get the right answer?

Sum together the partial output at position $i$ with the original input at $i+1$.

def fastscan(f, id_, a):

#space = len(a) * ' ' # for printing

#print(space, 'a=', a)

# base cases are same as reduce

if len(a) == 0:

return [], id_

elif len(a) == 1:

return [id_], a[0]

else:

# compute the "partial solution" by

# applying f to each adjacent pair of numbers

# e.g., [2, 1, 3, 2, 2, 5, 4, 1] -> [3, 5, 7, 5]

# this can be done in parallel

subproblem = [f(a[i], a[i+1]) for i in range(len(a))[::2]]

#print(space, 'subproblem=', subproblem)

# recursively apply fastscan to the subproblem

partial_output, total = fastscan(f, id_, subproblem) # ->[8, 12]->[20]

# partial_output = [0, 3, 8, 15] total=20

#print(space, 'partial_output=', partial_output, 'total=', total)

# combine partial_output with input to get desired output

ret = (

[partial_output[i//2] if i%2==0 else # use partial output

f(partial_output[i//2], a[i-1]) # combine partial output with next value

for i in range(len(a))],

total

)

#print(space, 'returning', ret)

return ret

def add(x,y):

return x + y

fastscan(add, 0, [2,1,3,2,2,5,4,1])

([0, 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 15, 19], 20)

# also works for other operators.

fastscan(select_positive, -math.inf, [1,0,-1,2,3,0,-5,7])

([-inf, 1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3], 7)

scan in SPARC¶

\begin{array}{l}

\\

\mathit{scan}~f~\mathit{id}~a =

\\

~~~~\texttt{if}~|a| = 0~\texttt{then}

\\

~~~~\left(\left\langle\, \,\right\rangle, id\right)

\\

~~~~\texttt{else if}~|a| = 1 ~\texttt{then}

\\

~~~~~~~~\left( \left\langle\, id \,\right\rangle, a[0] \right)

\\

~~~~\texttt{else}

\\

~~~~~~~~\texttt{let}

\\

~~~~~~~~~~~~a' = \left\langle\, f(a[2i],a[2i+1]) : 0 \leq i < n/2 \,\right\rangle

\\

~~~~~~~~~~~~(r,t) = \mathit{scan}~f~\mathit{id}~ a'

\\

~~~~~~~~\texttt{in}

\\

~~~~~~~~~~~~(\left\langle\, p_i : 0 \leq i < n \,\right\rangle, t),~\texttt{where}~p_i =

\begin{cases}

r[i/2] & \texttt{even}(i) \\

f(r[i/2], a[i-1]) & \texttt{otherwise}

\end{cases}

\\

~~~~~~~~\texttt{end}

\end{array}

Analysis of the Work of scan¶

Assume that function f is constant time.

subproblem = [f(a[i], a[i+1]) for i in range(len(a))[::2]]

takes $O(n)$ time

ret = (

[partial_output[i//2] if i%2==0 else

f(partial_output[i//2], a[i-1])

for i in range(len(a))],

total

)

takes $O(n)$ time

partial_output, total = fastscan(f, id_, subproblem)

reduces problem in half each recursive call

but there is only one recursive call, instead of two for, e.g., merge sort

Analysis of the Span of scan¶

Assume that function f is constant time.

subproblem = [f(a[i], a[i+1]) for i in range(len(a))[::2]]

With infinite processors, this can be done in constant span.

ret = (

[partial_output[i//2] if i%2==0 else

f(partial_output[i//2], a[i-1])

for i in range(len(a))],

total

)

With infinite processors, this can be done in constant span.

partial_output, total = fastscan(f, id_, subproblem)

reduces problem in half each recursive call

Runtime Analysis Results¶

$$W(n) \in O(n)$$$$S(n) \in O(\lg n)$$- surprisingly the same work and span of

reduce - even though we're keeping track of output for all prefixes.

scan is a popular primitive in parallel programming, used to solve many problems, including:

- evaluating polynomials

- quicksort

- search for regular expressions