Recurrences¶

Recurrences are a way to capture the behavior of recursive algorithms.

Key ingredients:

- Base case ($n = b_c$): constant time

- Inductive case ($n > b_c$): recurse on smaller instance and use output to compute solution

$b_c$ is the size of the base case problems

Actually recursion is a conceptual way to view algorithm execution, and we can reframe an algorithm specification to make it recursive.

Selection Sort¶

Consider selection_sort:

def selection_sort(L):

for i in range(len(L)):

print(L)

m = L.index(min(L[i:]))

L[i], L[m] = L[m], L[i]

return L

selection_sort([2, 1, 4, 3, 9])

How can we reframe it recursively?

def selection_sort_recursive(L):

print('L=%s' % L)

if (len(L) == 1):

return(L)

else:

m = L.index(min(L))

L[0], L[m] = L[m], L[0]

return [L[0]] + selection_sort_recursive(L[1:])

selection_sort_recursive([2, 1, 999, 4, 3])

What is the running time and why?

def selection_sort_recursive(L):

print('L=%s' % L)

if (len(L) == 1):

return(L)

else:

m = L.index(min(L))

L[0], L[m] = L[m], L[0]

return [L[0]] + selection_sort_recursive(L[1:])

$ \begin{align} W(n) &= W(n-1) + n \\ &= W(n-2) + (n - 1) + n \\ &= W(n-3) + (n - 2) + (n - 1) + n \\ &= ... \end{align} $

$\begin{align} W(n) &=& \sum_{i=1}^n i \\ &=& \frac{n(n+1)}{2} \\ &=& \Theta(n^2). \end{align}$

Asymptotic Proof¶

Why is it true that $\frac{n(n+1)}{2} \in \Theta(n^2)$?

Quickly, we can see that the highest order term is $n^2$ and so this makes sense.

$ \frac{n(n+1)}{2} = \frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2}$

However, we can prove it rigorously.

We can either use the limit theorem or prove it directly from the asymptotic definition by finding the necessary constants.

For practice, lets do the latter.

Asymptotic Proof that $\frac{n(n+1)}{2} \in \Theta(n^2)$¶

By definition:

$f(n) \in \Theta(g(n))$ if there exist positive constants $c_1$, $c_2$, and $n_0$ such that

$c_1 \cdot g(n) \le f(n) \le c_2 \cdot g(n)$ for all $n \ge n_0$

Thus we need $c_1$, $c_2$, and $n_0$ s.t.

$$c_1 \cdot n^2 \le \frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2} \le c_2 \cdot n^2 \qquad \forall \quad n >= n_0$$Left side

$$c_1 \cdot n^2 \le \frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2} \le c_2 \cdot n^2 \qquad \forall \quad n >= n_0$$What $c_1$ can we pick to make the left inequality true?

$$c_1 \cdot n^2 \le \frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2}$$If we let $c_1 = 1/2$, then

$$\frac{n^2}{2} <= \frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2}$$This is obviously true for all $n \ge 0$.

Right side

What about the other side?

$$\frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2} \le c_2 \cdot n^2$$What $c_2$ can we choose?

If we let $c_2 = 1$, then

$$\frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2} <= n^2$$Is this statement true?

Yes!

We have that:

$\frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2} <= n^2 \qquad \forall \; n \ge 0$

Thus $n_0 = 0$.

Putting it all together

Finally, we have that $ \frac{n^2}{2} \le \frac{n^2}{2}+\frac{n}{2} \le n^2$.

This is true $\forall \; n >= 0$.

We have chosen $c_1 = \frac{1}{2}$, $c_2 = 1$, and $n_0 = 0$.

Since we have found constants to satisfy the asymptotic definition, $\frac{n(n+1)}{2} \in \Theta(n^2) \quad \blacksquare$

Working towards more general recurrences¶

The recurrence for Selection Sort is somewhat simple - what if we have multiple recursive calls and split the input? (like divide-and-conquer algorithms)

We'll learn methods to solve recurrences for general recursive algorithms.

We will:

Get intuition for recurrences by analyzing their recursion trees.

Develop the brick method to quickly state asymptotic bounds for many recurrences by looking at the patterns of these trees.

Merge Sort¶

Let's look at the specification and recurrence for Merge Sort:

def merge_sort(lst):

if len(lst) <= 1:

return lst

mid = len(lst)//2

left = merge_sort(lst[:mid])

right = merge_sort(lst[mid:])

return merge(left, right) # implementation omitted

merge_sort sorts a list by recursively sorting both halves of the list and merging the results with $\Theta(n)$ work.

The recurrence for the work is:

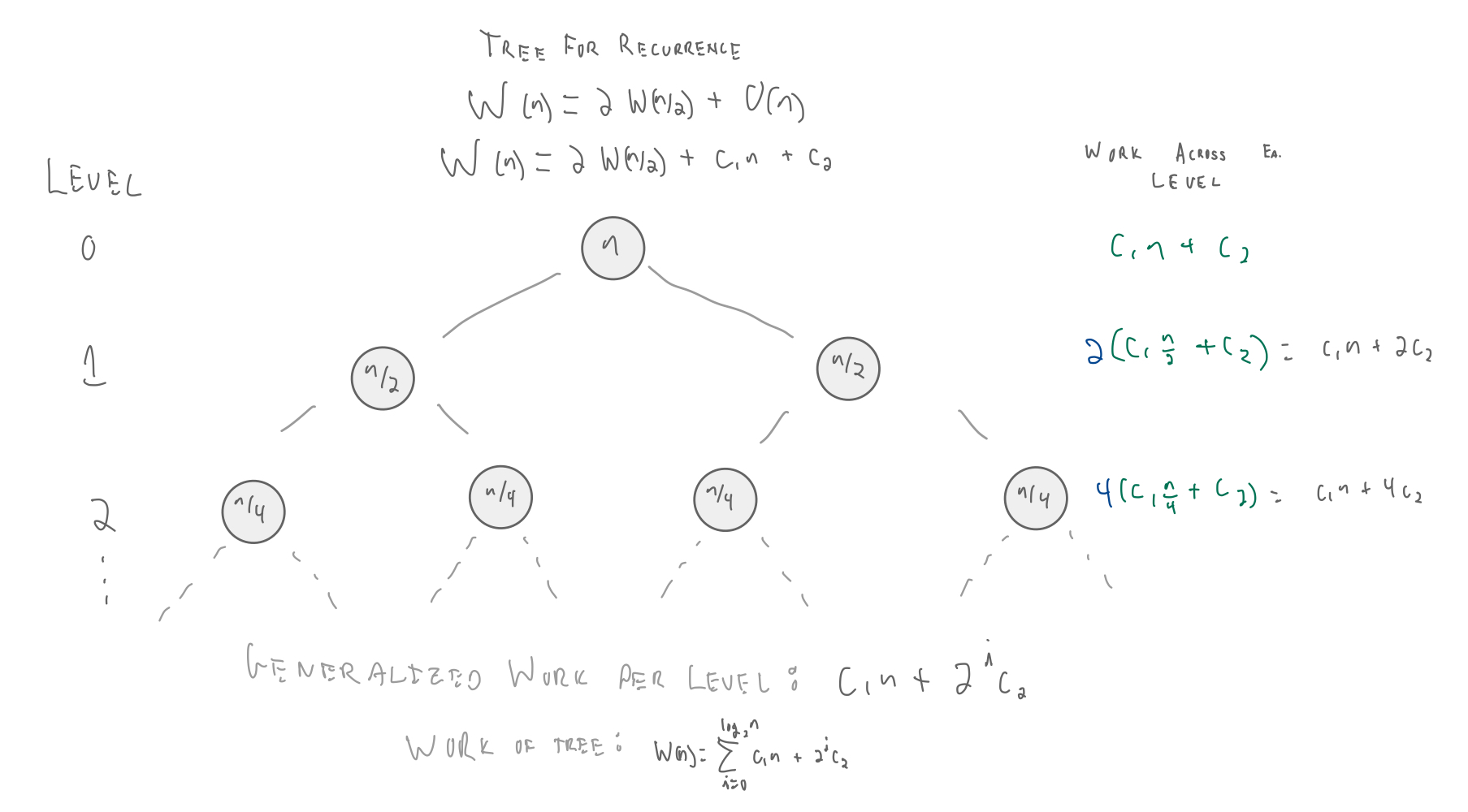

$$ \begin{align} W(n) = \begin{cases} c_b, & \text{if $n=1$} \\ 2W(n/2) + c_1n + c_2, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align} $$How do we solve this recurrence to obtain $W(n) = O(n\log n)$?

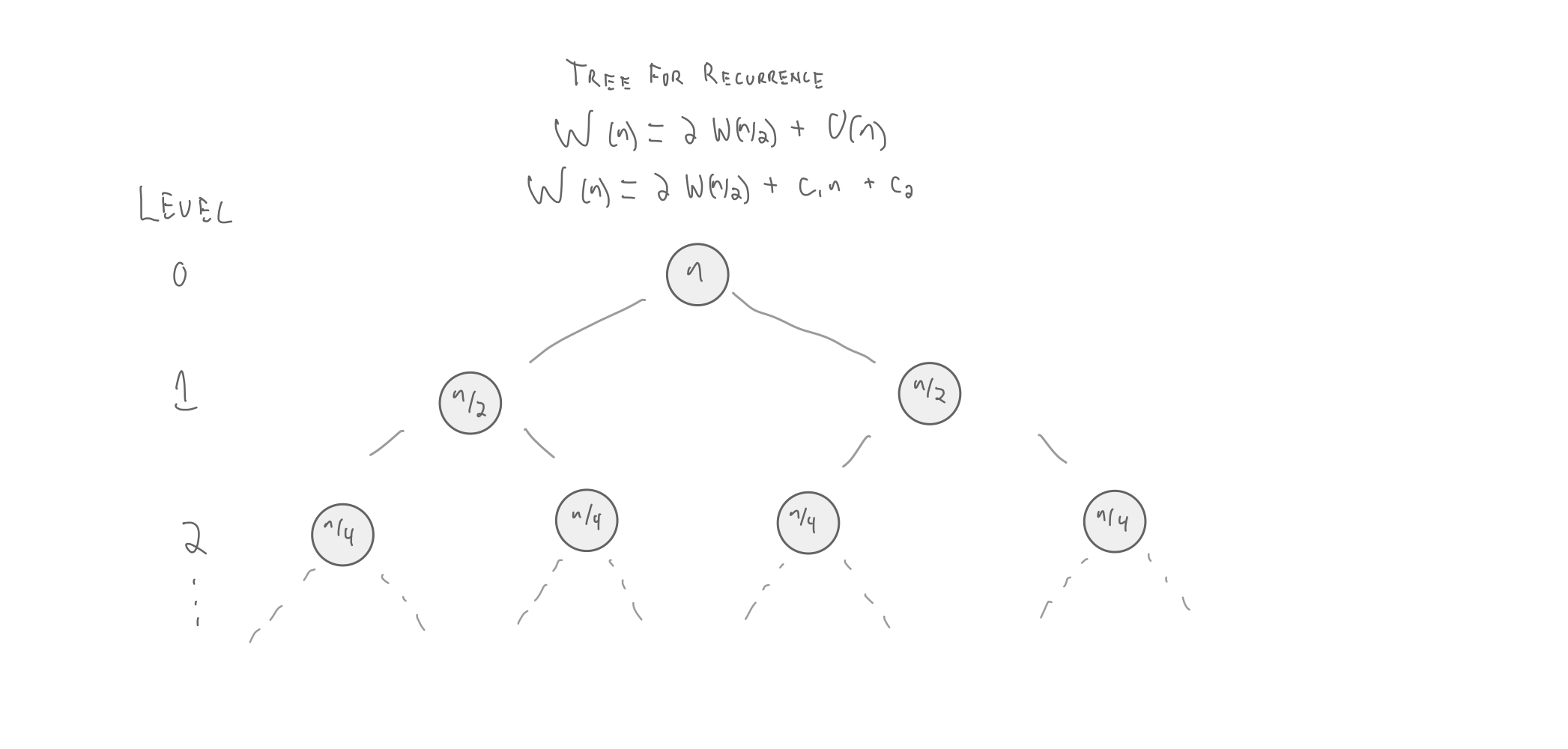

First, we draw the recursion tree for the recurrence.

Drawing the Recursion Tree¶

Solving the Summation¶

$$W(n) = \sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} (c_1n + 2^i c_2)$$$$= \sum_{i=0}^{\lg n}c_1 n + \sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} 2^i c_2$$To solve this, we'll make use of bounds for geometric series.

For $\alpha > 1$: $\:\:\: \sum_{i=0}^n \alpha^i < \frac{\alpha}{\alpha - 1}\cdot\alpha^n$

e.g,

$\sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} 2^i < \frac{2}{1} * 2^{\lg n} = 2n$

For $\alpha < 1$: $\:\:\: \sum_{i=0}^\infty \alpha^i < \frac{1}{1-\alpha}$

e.g,

$\sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} \frac{1}{2^i} < 2$

plugging in...

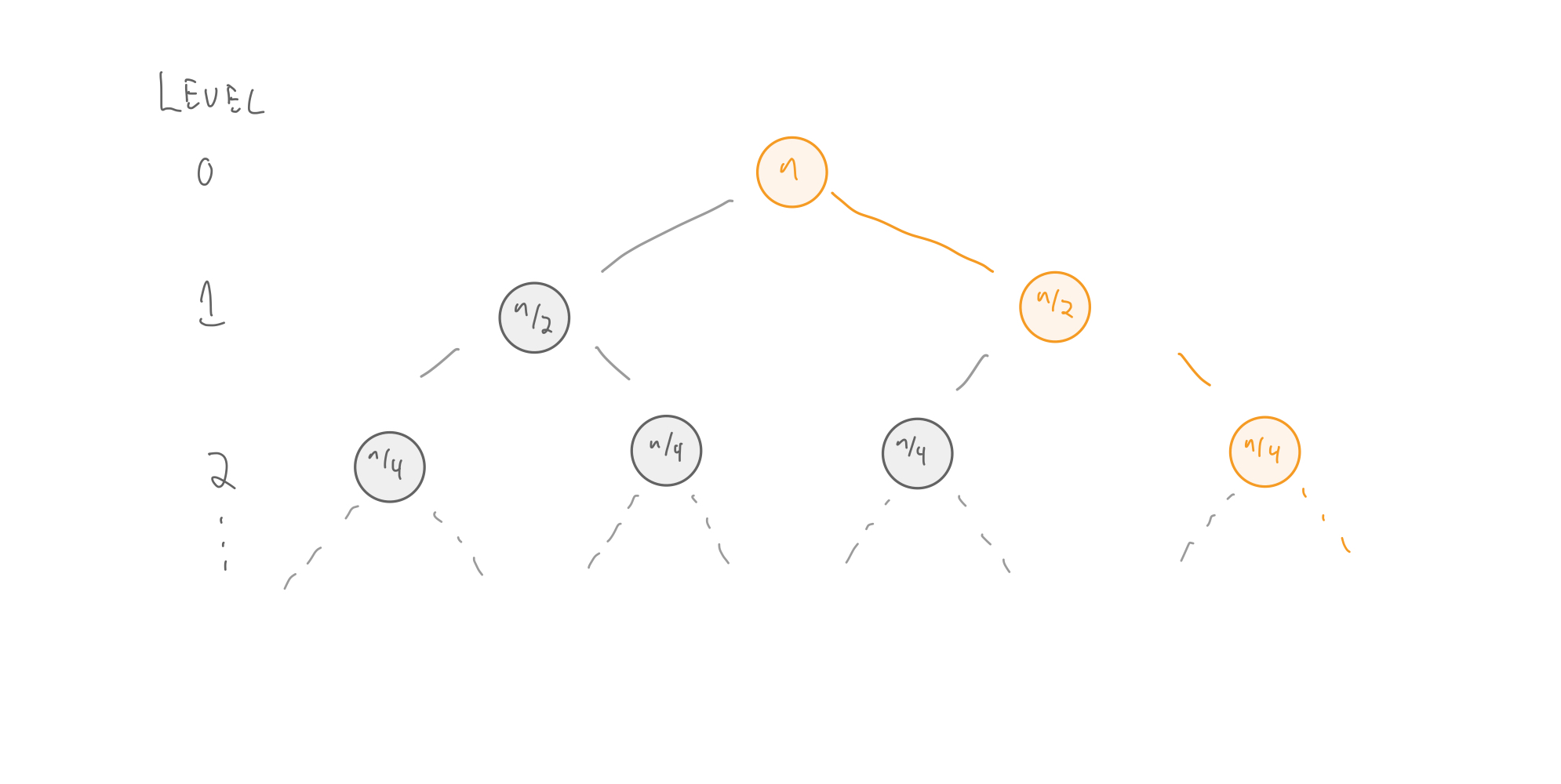

What about the span?¶

The recurrence for the span of Mergesort is:

$$ \begin{align} S(n) = \begin{cases} c_3, & \text{if $n=1$} \\ S(n/2) + c_4 \lg n, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align} $$Why?

The branching factor is $1$.

$S(n) = \pmb{S(n/2)} + c_4 \lg n$

$S(n) = S(n/2) + \pmb{c_4 \lg n}$

For span recurrences, this term represents the span of each subproblem.

A sequential merge algorithm requires $O(n)$ work and span.

However, there exists a parallel merge algorithm with:

- $W(n) \in O(n)$

- $S(n) \in O(\lg n)$

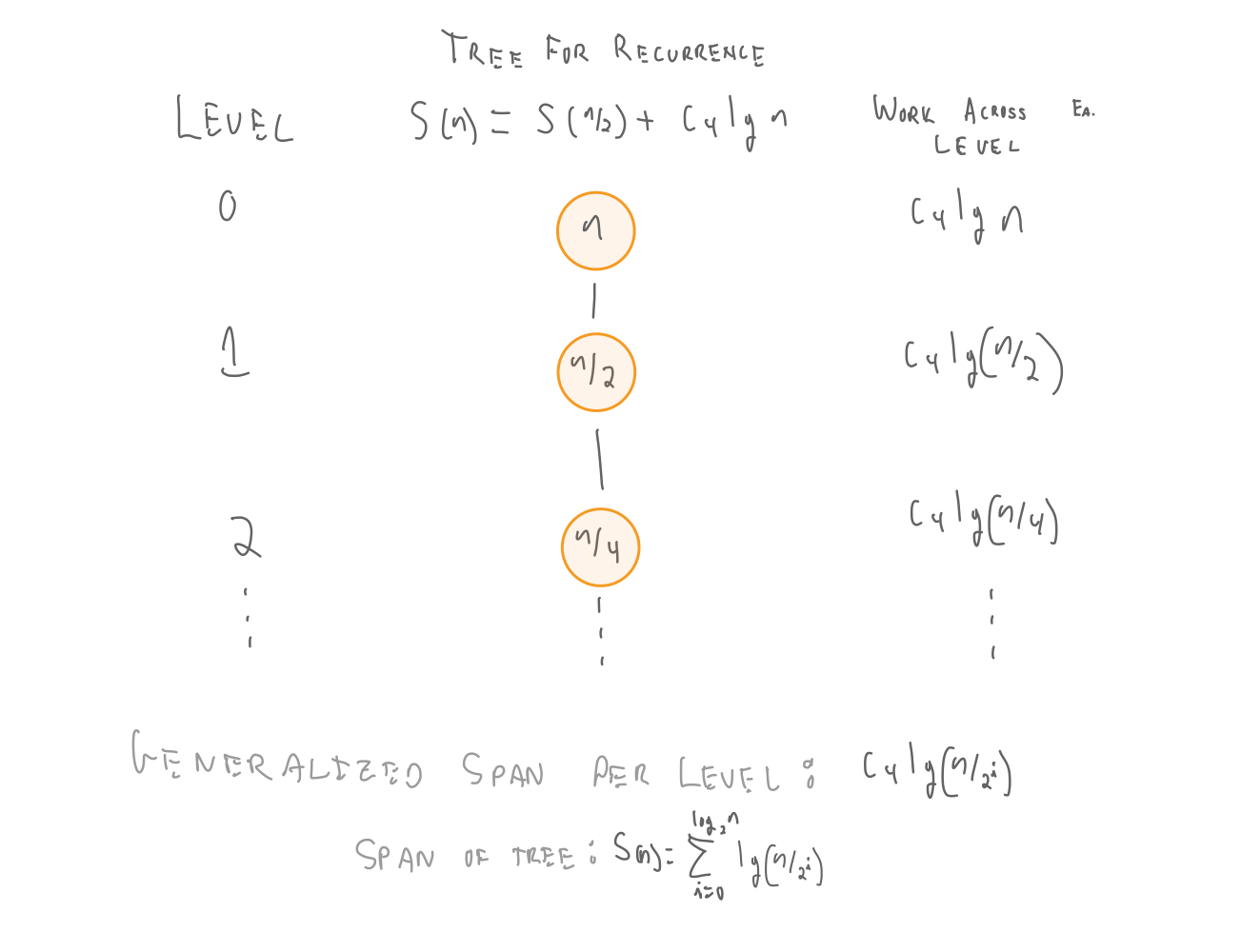

Solving the Span recurrence¶

$$ \begin{align} S(n) = \begin{cases} c_3, & \text{if $n=1$} \\ S(n/2) + c_4 \lg n, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$ \begin{align} S(n) & = & \sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} \lg\frac{n}{2^i}\\ & = & \sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} (\lg n - i)\\ & = & \sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} (\lg n) - \sum_{i=1}^{\lg n} i\\ & < & \lg^2 n - \frac{1}{2}\lg n * (\lg n+1) \:\: (\hbox{using}\:\:\sum_{i=0}^n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2})\\ & < & \lg^2n - \frac{1}{2}\lg^2 n - \frac{1}{2} \lg n\\ & \in & O(\lg^2 n)\\ \end{align}$

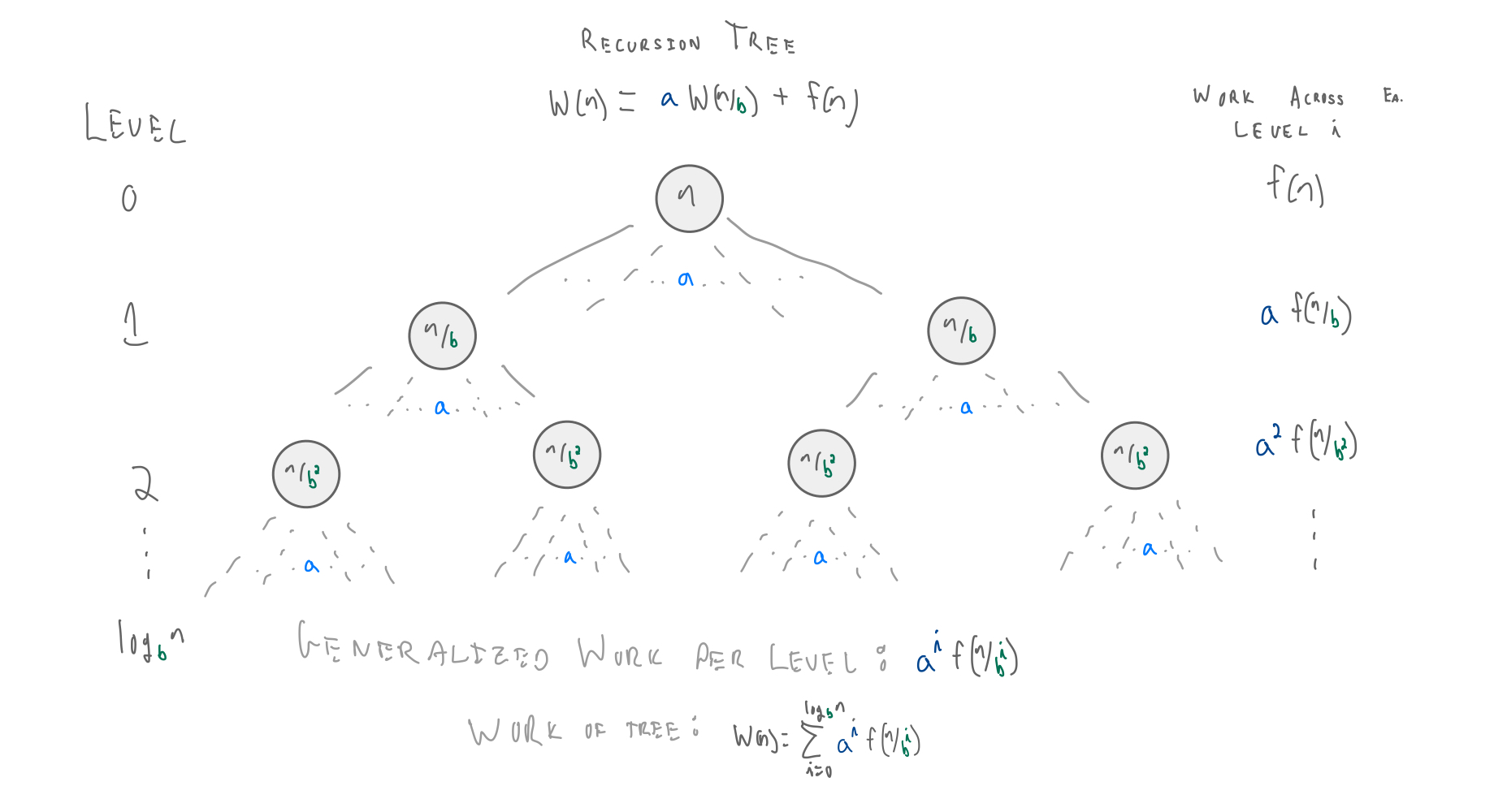

Divide and Conquer¶

Merge Sort is a divide-and-conquer algorithm.

A divide-and-conquer algorithm, at each step, divides the problem into subproblems, solves each, then combines the results to arrive at the final solution.

Recurrences can easily be written and interpretted from the perspective of divide and conquer algorithms.

- $a$ is the branching factor.

- $\frac{n}{b}$ gives us the sub-problem size at the next level.

- $f(n)$ is the cost of the work within each recursive call.

General Recurrences¶

More Practice¶

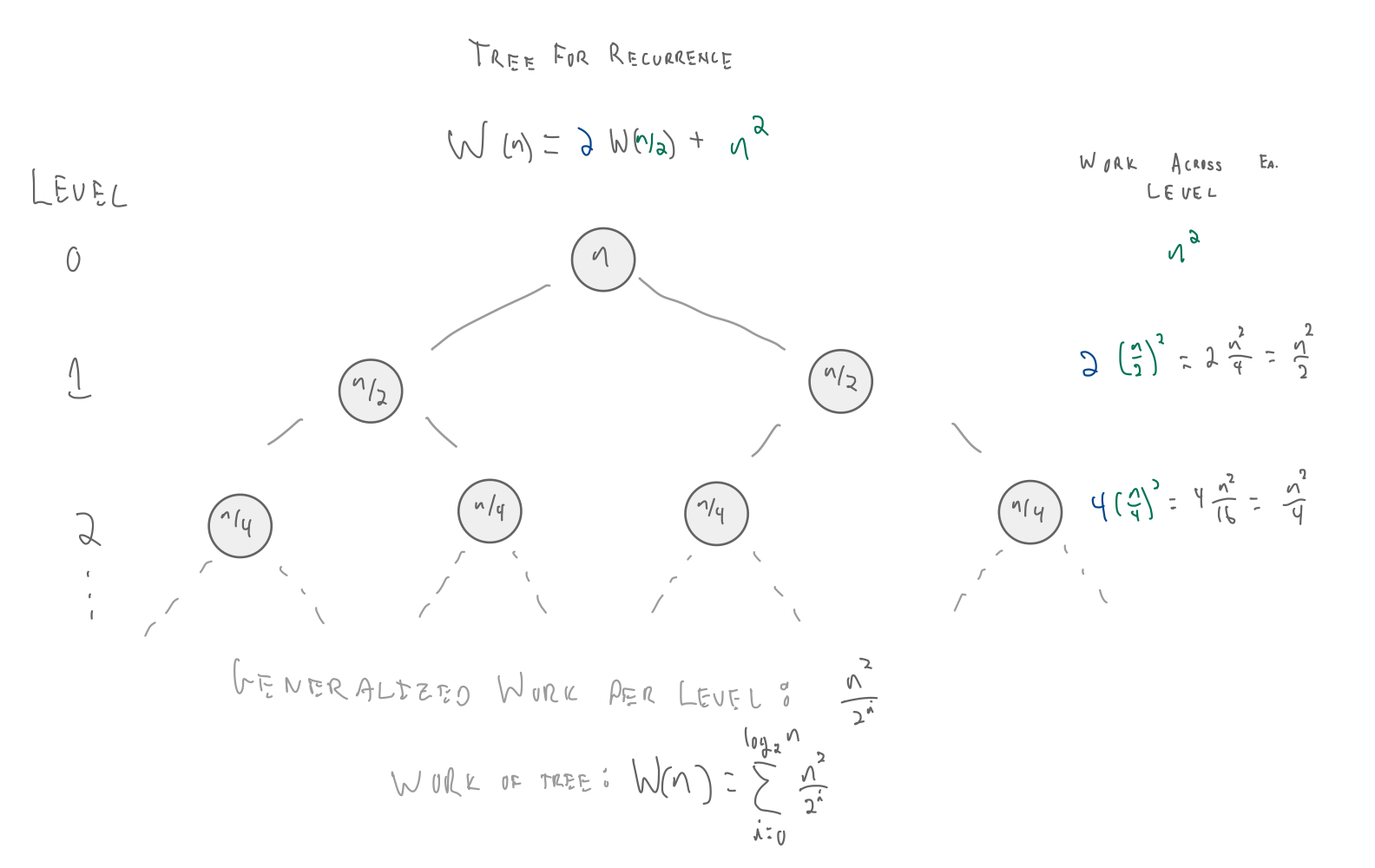

Another recurrence:

$$ W(n) = \begin{cases} c_b, & \text{if $n=1$} \\ 2W(n/2) + n^2, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $$What is the asymptotic runtime?

$W(n) = \sum_i^{\lg n} (\frac{n^2}{2^i})$

$= n^2 \sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} \frac{1}{2^i}$

$= c_1 n^2 \sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} (\frac{1}{2})^i$

To solve this, we can again use geometric series.

For $\alpha < 1$: $\:\:\: \sum_{i=0}^\infty \alpha^i < \frac{1}{1-\alpha}$

e.g., $\sum_{i=0}^{\lg n} \frac{1}{2^i} < 2$

$< 2 n^2$

$\in O(n^2)$

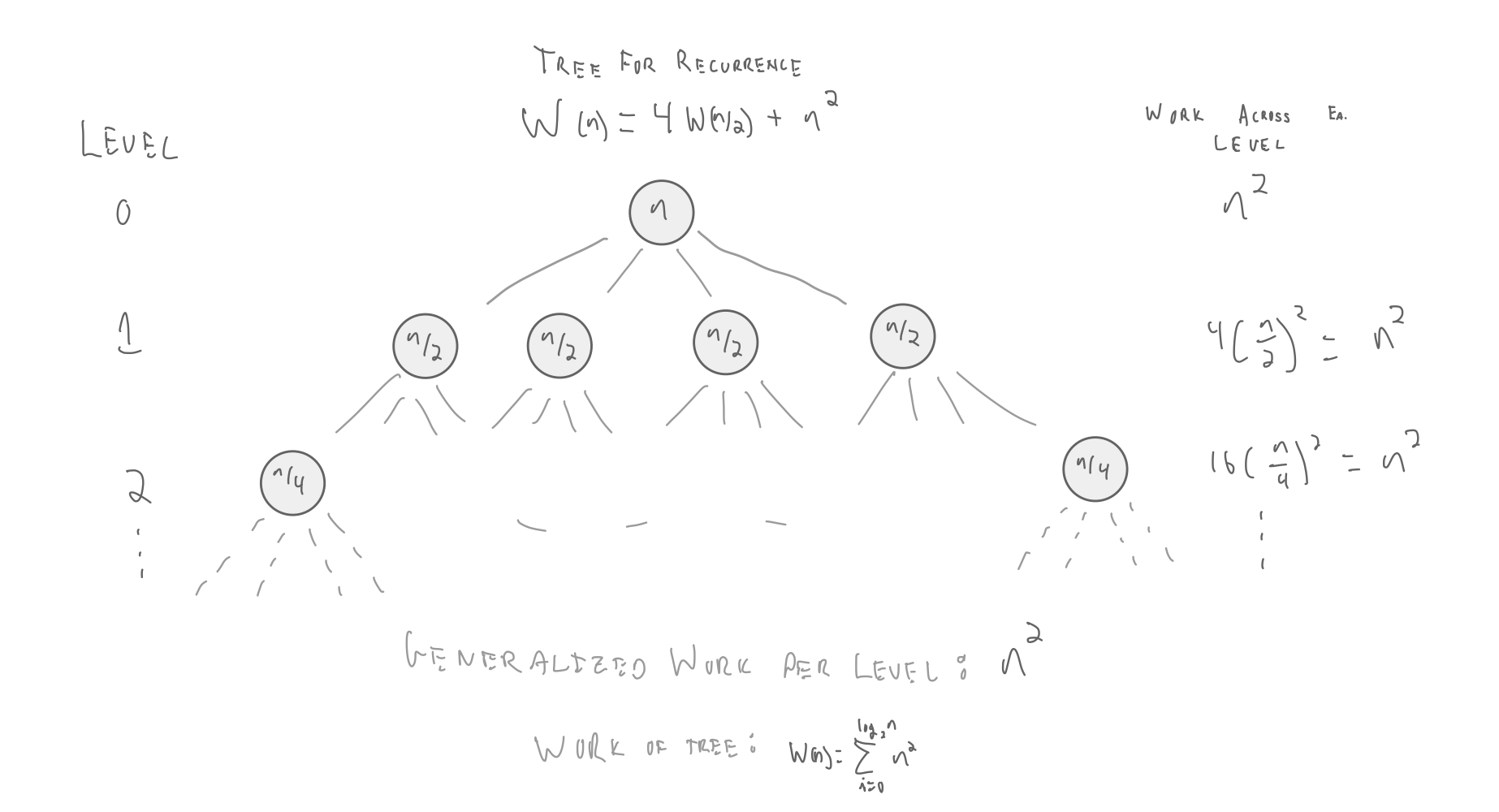

So what if branching factor is not 2?

still $\lg n$ levels. Why?

Because at every level we are dividing the problem size in half, so we still need $\log_2 n$ levels.

If we were dividing the problem size in thirds, we would need $\log_3 n$ levels

Coming up¶

We will general our recurrence solving strategies by noting common patterns in our recursion trees.